Date/Time

Date(s) - Monday 8 February 2021

8:00 pm - 9:00 pm

Categories No Categories

This talk was held via Zoom. There were 100 participants in the Zoom session.

The speaker

Andrew George is a long-term resident of Richmond and St Margarets. His academic background is as an immunologist, working at Imperial College London. He was Deputy Vice-Chancellor at Brunel University London, and currently supports a number of organisations (in the NHS, academia and charity sector) with research, education and ethics. He is also an executive coach.

Andrew has a MA from Cambridge, a PhD from Southampton and a DSc from Imperial, and was awarded an MBE for his work in research ethics. He has always had an interest in local history, and over the last few years has given a number of talks and walks looking at the characters and gardens associated with St Margarets.

The gardens of Twickenham Park

In his talk, Andrew George told us the fascinating story of the gardens in Twickenham Park that were located on the land that lies between Richmond Bridge and the River Crane.

In his talk, Andrew George told us the fascinating story of the gardens in Twickenham Park that were located on the land that lies between Richmond Bridge and the River Crane.

Twickenham Park was home to some interesting and important characters including Richard of Cornwall, Francis Bacon, Lucy Harrington and Thomas Vernon. Many of them were leading gardeners of their time, making a series of gardens in Twickenham Park that not only reflect the history of English gardening but were influential in garden design.

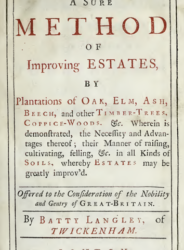

Generations of A-level students have suffered grievously from having to analyse John Donne’s poem celebrating Lucy Harrington’s garden in “Twicknam”, while Francis Bacon’s writings about gardens have not only influenced garden designers up to modern times but also inspired the first scientific and botanical gardens. Batty Langley was a pioneer in breaking away from the formal symmetry of early gardens, developing a rococo “arti-natural” approach to landscaping, while Thomas Vernon planted the first weeping willow in Britain in his garden.

Andrew described how the gardens developed from 1227 until 1854 when the Earl of Kilmorey sold much of the estate to the Conservative Land Society. He will put this in the context of the changing fashions in gardening, explain how gardens were used by their owners and tell us about some of the people who made them. It is a fascinating story that tells us a lot about the role and nature of gardens down the years.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________John Foley reports on Andrew George’s talk

“Twickenham Park? Don’t know where it is! Don’t you mean Marble Hill Park?” Not surprisingly, many local residents don’t know that, for centuries past, there was indeed a large estate known by this name, occupying a spacious chunk of land on the Middlesex bank of the Thames, stretching between today’s Richmond Bridge and old Isleworth and reaching back in the west approximately to where St Margarets Road is now.

But the estate was broken up 200 years ago, the land divided, sold off and developed piecemeal. It now forms part of the suburban area known to us as St Margarets and, to the north, old Isleworth. To appreciate the extent of this land before the 19th century you have to think away the existence of the railway (which arrived in the 1850s and the A316, a youngster only 90 years old, both of which cut straight across.)

Twickenham Park has a considerable history. The earliest notable resident was Richard, Earl of Cornwall, who in 1227 was granted land at Old Isleworth where he built a manor house and vineyard, surrounded by a moat. A strong, ambitious character, Richard was elected at one time “King of the Romans” but, being the weak King Henry III’s younger brother, in 1263 he attracted the attention of Simon de Montfort who with his rebel barons attacked and damaged the settlement (and was later punished by a fine of a thousand marks).

One hundred and fifty years later, in 1415, Henry V founded a chantry at Isleworth to atone for the alleged murder of Richard II: the Order of St Bridget of Syon. In 1431, the Bridgetines started to build their abbey, where they stayed until ejected a century later by the Reformation. Syon Abbey had an orchard as well as two cloister gardens. Andrew told us that having been expelled to Lisbon, the Bridgetines eventually returned to Plymouth.

Then the Bacon family came: the most famous occupant of Twickenham Park has to be Francis Bacon (who was bequeathed the house and land, where he lived very happily, partly to escape plague-infested London, until 1608. Bacon was a polymath an and influential lawyer, a Queen’s Counsel. His legacy includes philosophy, a pioneer of “scientific methodology”, legal writing and theorising which influenced America’s founding fathers and the Napoleonic code; and before being impeached and (briefly) locked in the Tower (after which he left to live in St Albans), Bacon wandered his grounds and wrote some of his famous literary essays. Though we don’t know whether his musings on gardens were actually written here…”God Almighty first planted a garden. And indeed It is the purest of human pleasures. It is the greatest refreshment to the spirits of man; without which, buildings and palaces are but gross handiworks…”

Andrew stressed the connection of Twickenham Park’s gardens to the general development in the history of creative English landscape gardening. Bacon departed in 1608, but several subsequent owners were passionate gardeners. Lucy Harrington, Countess of Bedford, the next owner, took over development of Bacon’s garden and (we believe) rebuilt the house in a brick Jacobean style with towers at each end. She was the confidante of James I’s queen, Anne of Denmark and of her children Prince Henry Stuart (who died young, leaving ambitious plans for a new garden at Richmond Palace) and Princess Elizabeth, the future tragic “winter Queen” of Bohemia.

A plan by Smythson and a painting show how gardens surrounded the house, including a kitchen garden at the side, the symmetrical design contrasting with the wildness of untamed nature beyond. All sorts of fruit and vegetables were grown, squash, pumpkins, marrow, runner beans, even melons, turnips and cabbages for pickling in sauerkraut (a Dutch influence); there were also “viewing” mounts of between 6 to 8 feet high which you could climb up by steps, for an aerial view (including that across the river to Richmond Palace.)

Lucy Harrington remained at the centre of garden design which she continued at Moor Park where she went in 1618, while the next owners, the Countess of Home and especially Sir Thomas Vernon (1666 to 1726) developed the gardens further. Vernon, a director of the South Sea Company, acquired even more land. He became the landlord of both Henrietta Howard at Marble Hill and Alexander Pope. Moreover, he employed the architect Batty Langley who whilst influenced by the then French fashion of forming long avenues of trees to “control” the landscape and to make a grand impression ,in his individual way continued the transformation of the gardens toward the Capability Brown English-type landscape. Vernon also grew the first weeping willow, sending seeds to Pope.

The final passionate gardener owner was Harriet Pelham Hollies, Duchess of Newscastle (1701 to 1776); but her creative work was mainly at nearby Claremont where she employed the principles of Orlando Bridgman, William Kent and of course Lancelot Brown during the high noon of 18th century landscape garden design. But during her custodianship at Twickenham the garden appears as a “capability” landscape which you see surrounding a four-storey red brick Georgian mansion in a 1790 painting, with horses grazing and people strolling.

But, sadly, not for much longer. We are told that the house was old and delapidated. It was sold in 1809 and the buyer partitioned up the estate. New smaller villas were built, at various points, but the integrity of the park was lost. And the despoilation was completed in the 20th century.

So. thanks to Andrew George’s comprehensive presentation, while you may now know roughly where Twickenham Park was, what is there left to visit ? Not much; only the Victorian development created by the Conservative Land Society in the 1850s remains (around Ailsa Road, St Peters Road and St George’s Road) which you can stroll around in the footsteps of Francis Bacon. You can see the brick Victorian mansions with large domestic gardens, all rather charming. Of, a previous civilised bygone age there is even a smidgen of the old park and lake hidden in trees. But mind; this is private property, and only to be viewed by invitation!