The original version of this article by Peter Flower was published in Richmond History 31 (2010).

In the halcyon summer of 1914 there appears to have been little thought at The Vineyard Church, Richmond of the looming political crisis that was to engulf Europe; the minutes of the church meetings record the usual matters of these gatherings – decisions about those joining the church, sales of work for the London Missionary Society, visits by outside preachers and the like.

Then war was declared against Germany on 4 August 1914 following the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on 28 July 1914 in the Balkans.

As is well known, patriotic fervour swept across Britain and men enlisted to fight for King and Country. At the church meeting on 1 October 1914 some seven weeks after the declaration, the congregation was told formally the names of those from the church who had enlisted; this was prompted by a request from the Congregational Union of England and Wales for the number who had enlisted. The minute book records that 16 men had joined up, five members of the congregation and eleven from the Vineyard Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Association. Brotherhood. This was a fellowship group that had been in existence at the church since 1893. [See ref 1] The sixteen had joined units ranging from 15th Hussars to the 6th (Cyclists) Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment in late August and during September. A number were reservists –an Assistant Paymaster, two sergeants and a 2nd Lieutenant; one had joined the Royal Navy and was a seaman on HMS Garland but quite naturally a number had joined the local regiment, the East Surrey Regiment.

But in fact there were others who had enlisted but whose names were omitted at the meeting; at the next church meeting on 29 October a further twelve names were added, making 28 men in total. A full list of their names is given in Appendix 1. Remarkably, only one of those who enlisted at the outbreak of the war was killed. He was 2nd Lieutenant Arthur Ewart-Jones from the Welsh Regiment who was killed less than a year later in 1915.

The advent of war had an impact in other ways. The Ladies Sewing Meeting was formed to “relieve suffering caused by the war” and had an average weekly attendance of 40. At the 1 October church meeting, it was reported that 90 garments had been sent to the Red Cross and another 100 garments to the Belgian refugees. At the next church meeting at the end of October it was reported that a concert held in the church, in conjunction with the Vineyard Brotherhood, had raised £21 in aid of the Belgian refugees. Clearly the plight of those displaced by the German army’s sweep through Belgium had touched many people’s hearts. Apparently this was the first effort of this kind in the borough and the church was “crowded to the doors”.

The work of the Ladies Sewing Meeting continued with an attendance averaging 35. About 500 garments had been made over 16 weeks by the beginning of December. 100 garments were given to the Belgian refugees, and 200 to the Red Cross. The latter organisation had praised the ladies for the “quality of their work”. Support for the men serving in the forces was in the form of a parcel sent from the church to each man who had enlisted. This was noted as 24 men so it is unclear if four of the original list compiled had returned to civilian life or had perhaps been noted in error. While all involved in this initiative were commended, the minutes record that three ladies were “particularly worthy of notice”: Mrs Hall, Mrs Hutt and Mrs Lewis.

At the outbreak of the war, the Vineyard Brotherhood had pledged to contribute £1 per week to the Richmond Emergency Fund and by the end of the year had raised £30 5s 0d with the aid of those in the church; the purpose of the fund is not clear but is likely to have been to support work with refugees. At the beginning of January 1915 a special day of national intercessory prayer was called for by the King. The day was set as Sunday 3 January and churches across the country and, indeed in other parts of the Empire, were asked to observe it. The congregation agreed to use the set order of service published for the occasion which has been preserved in the church archives; it ended with the National Anthem.

The direct impact of the war until now did not appear to have been great; men from the congregation were serving in the forces, more had joined up since the initial rush in 1914, funds were raised for war work, soldiers stationed nearby were ministered to. Early in 1915 it was reported that the church insurance premium had been increased due to Zeppelin attacks on London.

Then in the spring of 1915, 50 wounded soldiers from the military hospital at Isleworth were entertained for tea by the Girls Club and in June the Mayor‘s offer to speak to the congregation about the War Savings Association was taken up.

Arthur Ewart-Jones

The death of the first serviceman from the Vineyard Church occurred on 8 August 1915 during the ill-fated eight-month Gallipoli campaign. This campaign was the brainchild of Winston Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, to force Turkey out of the war and relieve the deadlock on the Western Front. 2nd Lieutenant Arthur Ewart-Jones, aged 28, was serving with the 8th Battalion of the Welsh Regiment. It is possible that he was killed during the Sulva landings which started two days before his death. His name is commemorated on the Helles Memorial on the peninsula as he had no known grave. No mention is made in the church meeting minutes of his death. This may have been because his family was not local but lived in Wales. His father was a minister in a church in Caernarvonshire. Before he enlisted, Ewart-Jones was a hydraulic engineer. In the 1911 Census he was shown as being one of three boarders staying at 39 Old Deer Park Gardens, Richmond.

Nothing more is recorded in the church records until in November 1915, some 15 months after outbreak of the war. A large meeting was then held in the basement of the church where Sunday School classes normally took place. A visiting minister from Kensington spoke on his thoughts about the war and the pastor of the Vineyard read out extracts from letters written by some of “our boys across the sea” while the church choir sang a collection of songs. The church ladies provided refreshments and, as the minute taker recoded, “prettily decorated the room for the occasion”. But nothing was recoded of what was happening to the men on active service. However, in December the needs of those troops billeted in the area were recognised and a special service was held on Sunday mornings for them which was conducted by the Richmond Free Church ministers in turn. Upwards of 200 men attended.

The King’s exhortation for a day of prayerful intercession was taken up again on the first Sunday of January 1916 with the congregation using the set service suggested – ending, as in the previous year, singing the National Anthem. On this occasion a special collection was made in aid of the Red Cross and St John Ambulance. As the year unfolded, further deaths occurred in the fierce fighting along the Western Front.

Sydney Deayton

There are more than 54,000 names on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres commemorating those missing in action from the Ypres Salient during the First World War; one of those names is that of Private Sydney Deayton from the Vineyard Congregational Church who served with the Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. So how did Sydney end up enlisting in Canada and being killed during a German offensive in June 1916 in the Ypres Salient?

Sydney Prior Dayton [in official records his names are spelt variously as “Sidney” or “Sydney” and “Prior” or “Pryor”] was the son of Alfred, a grocer by trade, who lived in Twickenham with his wife Martha and their five sons and one daughter. As the 1901 census gave Alfred’s occupation as Managing Director of Deayton Stores Ltd his retailing business had evidently prospered from the original grocer’s shop that he started with his brother. The Vineyard Church records show that he became a member of the church in April 1891 and was appointed as a deacon soon after. In May 1893 16 new members were proposed for church membership at a special church meeting; two of these were Sydney Deayton, aged 15, and Edward Deayton, aged 13. As membership was dependent on a confession of faith it is clear that both were professed Christians.

The Census Records of 1901 show Sydney, by now aged 23, still living at home with the rest of his family and working as a clerk in his father’s store. But in 1907 he emigrated to Canada and sailed from Glasgow to Montreal on the Allan Line Royal Mail Steamship ‘Corinthian’ together with 286 other passengers. The ship’s records do not show his occupation or age and for some reason he was classified as being “Scotch”. His destination was Toronto, Ontario.

At a meeting of the Vineyard Church back in Richmond in June 1915 it is recorded that a request had been received from the Minister of the Congregational church in Ottawa, Canada, asking for the formal transfer of church membership to the church in Ottawa of a Sydney “Mason”. This man was now stationed in the city as a trooper and undergoing military training. Toronto and Ottawa are not far distant. It seems likely that the minute taker misheard the pastor and that this referred to Sydney Deayton. A search has found that there are no entries in the Canadian Army records of a Sydney Mason. The Vineyard Church Minister, Archibald Johnstone, said that as it was likely that once his training was finished Sydney would be transferred to fight in Europe, and while warmly commending his “call to the church” in Ottawa, suggested to his brother minister that formal transfer of membership should be delayed until his permanent place of residence became clearer, especially as he might be posted back to his “native country”.

This correspondence took place in June 1915; perhaps Trooper Deayton’s training during that summer was informal as in September 1915 the Canadian army records show him enlisting at the Toronto Recruiting Depot, Ontario in the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. This regiment had only been formed the year before. Princess Patricia of Connaught, the daughter of the Duke of Connaught, Canada’s Governor General, was its patron. She became Colonel-in-Chief in 1918.

Sydney’s Army Attestation Record shows that he was single, still a salesman and that by now his father, as next of kin, was living at an address in Bristol, possibly having retired there. The London Gazette records that the Deayton family business floundered in 1913 and went into liquidation in 1915. Sydney’s date of birth is given as 1882, making him 32; in fact, from the British Census Records it is known that he was actually 38. Why he should have given a false date of birth is unclear; the upper age for enlistment at the time was 45 so there was no obvious reason to lie about his age. However, the biggest hurdle for most older men in enlisting was apparently health and dental issues. Maybe he thought he might stand a better chance of being accepted if he said he was younger. In any event, the Medical Officer, Captain Barton, who examined him, noted a circular scar under his right wrist but passed him as fit for duty. He was therefore sworn in and enlisted into the 4th University Company on 22 September 1915. Curiously, his religious denomination was listed as C of E [Church of England] and not Congregationalist. Why he put this down is not clear as he obviously considered himself a Congregationalist by his admission to the Vineyard Church back in 1893 and his application to transfer his church membership to a Canadian church made a few months earlier. Perhaps it was a mistake on behalf of the recruiting officer.

Sydney arrived back in England a few months after joining up and was posted to the 11th Battalion in December 1915; it was at this time that the regiment became part of the newly formed 3rd Canadian Division as part of the 7th Brigade. Other units of the Brigade included the Royal Canadian Regiment, the 42nd Battalion (Black Watch) and the 49th Battalion (The Edmonton Regiment). Whether Sydney managed to see his family during home leave is not known. He crossed to France on 24 March 1916 and on 9 April he joined the regiment in the Sanctuary Wood sector of the Ypres Salient in Flanders. He was therefore at the forefront of the German offensive to overrun Mount Sorrel which began at 6.00 am on 2 June 1916.

The Canadian troops held what little high ground there was which gave them observation over the German positions but made them a prime target for the German troops to overrun. The Canadian troops experienced a terrifying ordeal of intense bombardment that lasted four hours. Trenches vanished and the troops sheltering in them were annihilated. A German eye-witness to the general conflict wrote that: “The whole enemy position was a cloud of dust and dirt, into which timber, tree trunks, weapons, and equipment were continuously hurled up and occasionally human bodies”.

During the morning the deluge of fire continued in intensity and just after 1.00 pm the Germans exploded four underground mines short of the Canadian trenches on Mount Sorrel and then attacked. In bright sunlight the Germans advanced in four waves spaced about 75 yards apart. There was fierce fighting, much of it hand to hand and most of the Canadian positions were overrun.

Sydney Deayton was later reported missing in action, as were all the other men in his section. The news would have taken a little time to reach his 74-year-old father as his next of kin in England. No doubt the family hoped against hope that he had been taken prisoner. The church was informed that Sydney was missing in action “on the Western Front”.

His section had been positioned in a bay on the extreme right of a trench called Trench 62 during the attack but it transpired later that they were all killed as a result of being heavily bombarded by trench mortars. Unlike some who were killed and whose names are recorded on the church war memorial, there is no record in the local Richmond newspaper of his death. Sydney’s service had lasted little more than eight months from enlisting in Ontario to being blown up defending a small piece of a Flanders field. The Patricias had more than 400 casualties including 150 killed during this engagement. Besides Sydney and his comrades, among the dead was Lt. Colonel H C. Butler, their commanding officer.

Percy Kentrzinsky

A month later, on the first day of the battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, Rifleman Percy Kentrzinsky serving with the 1st/16th battalion of the London Regiment (Queen’s Westminster Rifles) was killed. As with Ewart-Jones, and Deayton, Kentrzinsky’s body was never found and his name is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial in Northern France, together with 72,000 others. Initially reported missing, official confirmation that he was presumed killed did not come though until May, the following year. His mother, Kate, who was widowed and lived in Townsend Road, Richmond, was deeply affected by his death. The congregation expressed its deep condolences to her and others in her family at a church meeting at the end of May 1917; as recorded in the minutes it was stated that he was a “valued member of the church choir and Sunday school”. He was aged 23. In August 1917, just over a year after his death, Mrs Kentrzinsky asked permission for a memorial brass to be placed in the church to commemorate him. This was granted unanimously.

Horace Stratfold

Casualties from the church continued. Horace Stratfold, a Gunner with A Battery (190th Brigade) of the Royal Field Artillery, was next, killed early in September 1916 fighting at Flatiron Copse, Mametz in Northern France as part of the continuing battle of the Somme. Aged 34,. his parents lived in Bury St Edmunds, but he left a wife, Nellie, who lived in St Margarets.

Frederick Law

Frederick Law, a Rifleman with the 8th Battalion of the London Regiment (Post Office Rifles) was the third to be killed a month later in October 1916. Aged 30, he left a widow, Alice, living in York Road, Richmond. The 47th (London) Division was involved in fierce fighting in early October at Warlencourt, the Butte de Warlencourt and Eaucourt-L’Abbaye and it likely Law was killed in this offensive. He is buried at the Warlencourt British Cemetery together with over 3000 others from the United Kingdom and the then British Empire.

Alfred Aylett

1917 saw the relentless toll of the war continuing but there is no record of a call to national prayer that January and if the Ladies Sewing Meeting still persevered with their clothes making it is not mentioned in any church records. Lieutenant Allchen, who had enlisted in 1914 and was with the Army Pay Corps, was reported in the Richmond & Twickenham Times in January as being one of a number mentioned in despatches by Field Marshall Haig for “distinguished and gallant services and devotion to duty”.

But in February, another death became known. This was Private Alfred Aylett, aged 23 and serving with the 1st Battalion of the Honourable Artillery Company, who died at Beaumont Hamel, in Northern France. The village of Beaumont Hamel was an objective

of the 1 July attack in 1916 but was not captured until November. Aylett’s unit must have been holding the line there until the Germans withdrew in the spring of 1917 to the Hindenburg Line. He is buried at Ancre British Cemetery, Beaumont Hamel.

Aylett’s father worked as a horseman for the Corporation and lived at the Corporation Depot in Lower Mortlake Road. Little is known of most of those killed from the Vineyard Church but because Aylett’s death was reported in the Richmond and Twickenham Times more details have survived. His father, also called Alfred, was married to Eliza. Alfred junior was their only son. He attended the Wesleyan School in Kew Road. Later he was employed as a waterproof salesman in Piccadilly. He had a sister, Mabel. A member of the Vineyard Brotherhood, Evelyn Road Mission and Order of Oddfellows like his father, Private Aylett joined up in November 1915, aged 21 and trained in Richmond Park and Blackheath. He left for France in June 1916. At the time of his death eight months later, under fire he led a party with pack animals carrying rations up to the trenches. The newspaper reported that he walked steadily under heavy shelling until he was killed “outright” by a shell at 3.30 am. His Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Wollans, wrote to his parents saying that “he was popular in his section”. He apologised to Aylett’s parents for not writing to them sooner but he had “been going up every night for 10 nights and generally for at least 8 hours and had not had a single opportunity to write before”. The life expectancy of junior officers on the front line was short, their role extremely stressful, and their duty of having to write to the bereaved next of kin was a particularly difficult one.

Wilfrid Browne

Private Wilfrid Browne, aged 23, serving with the 13th Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps, was the next Vineyard casualty on 6 November 1917. His death was the first to occur in the Ypres Salient in Belgium. His father, William, and mother, Martha, lived in King Street, Richmond. Like Aylett, his death was reported in the local press. He was the fifth man to be killed from King Street which in itself brings home the devastation that the war had on ordinarily life away from the front. Educated at the Wesleyan School in Kew Road, he was a classmate of Aylett, and he was also very much part of the church fellowship, being the Secretary of the Vineyard Sunday School and a member of the choir. Browne enlisted in July 1916, and had his first leave in October 1917 before going back to France on 23 October, his 23rd birthday. It was reported that he was killed instantly while bringing in wounded under fire. He is buried at Menin Road South Military Cemetery.

The church was deeply distressed to hear the news of his death from the pastor at a meeting on 28 November 1917. Wilfrid Browne was very well respected and one of the congregation said that as his school teacher he recognised his spiritual maturity. A request made by the family for a memorial brass to be erected was granted. A service to dedicate a brass wall plaque in his memory was held the following year in 1918 conducted by the Rev Aveling who preached from Matt 17 vs. 47: “He saved others…” on performing his Christian duty to give his life for others. The plaque states he was a “Chorister and Secretary of the Sunday School”.

Francis and George Marshall

One of the two Marshall brothers from the church was the next to be reported killed the day after this meeting on 29 November 1917; Francis was 25 and serving as a Rifleman with the 16th Battalion of the London Regiment (Queen’s Westminster Rifles). He was killed at Hermies on the Somme. His younger brother, George, who was a Private with the 4th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, was killed a year later in October 1918, also on the Somme. Both brothers were born in Brighton where their father, Frederick, was an optician. Besides the brothers, their mother Mary had a daughter, Idina. The family later moved to Ealing in West London. The 1911 Census showed that Francis lived at 26 Onslow Road, Richmond and was a clerk in a bank. George enlisted in Ealing but lived in Brentford. The death of both sons must have been a devastating blow to the Marshall family.

Reginald Perrin

Meanwhile, the mundane work of supporting those at the front continued; as the war entered its fourth year in January 1918 £7 was donated towards the fund for sending parcels to men “with the colours”. 24 substantial parcels were sent to men associated with the church or Sunday School. Private Percy Hooke wrote to the church in May 1918 to thank the church for expressing their sympathy to him and to report he was making satisfactory progress – presumably from his war wounds. But casualties still continued. 1918 saw the death of two soldiers from the Vineyard who were decorated for bravery – Captain Reginald Perrin who was awarded the Military Cross and Pioneer Frank Lenzer who was awarded the Military Medal.

Captain Perrin was the second officer from the church who was killed in the war. He enlisted as a private but was later commissioned as an officer and placed on the General Army List. He served with the London Regiment and Seaforth Highlanders and then as Brigade Major with the 7th Infantry Brigade, 25th Division at Infantry Brigade Headquarters. He was killed, aged 34 on 27 May 1918 during the battle of Aisne and Marne. His body was never found and he is commemorated on the Soissons Memorial, Aisne, France. His mother, Mrs Harriet S Perrin, lived near the church at 84 Mount Ararat Road, Richmond. His father, a merchant tailor, had died before the war. As a boy, Reginald had lived with his two brothers and sister at 31 Halford Road, again, near the church. No citation has survived to show the details of when and why he was awarded the Military Cross. It is unclear why his decoration is not shown on the church war memorial.

Frank Lenzer

The last soldier from the church whose name appears on the war memorial is Frank Lenzer who died on 4 November 1918 aged 28 in Beirut, six days before the armistice was declared. He enlisted as a Pioneer, [Private] in the Royal Engineers and served in the 10th Cavalry Brigade Signal Company. Other units with whom he served were the 34th Berkshire Yeomanry, 6th Mounted Battalion Signal Troop and the 6th Brigade Signal Troop Royal Engineers. He was the only son of Francis Charles and Eliza Lenzer of 91 Chester Terrace, Henley on Thames; his father was in the hotel business. Lenzer in the 1911 Census is shown as living at the Red Lion Hotel, Henley on Thames where his father was the manager. He was a bank clerk. Posted to Egypt in April 1915, he was awarded the Military Medal there on 10 April 1918. He is buried in Beirut War Cemetery, Lebanon. A memorial brass in the church states that he was a member of the Vineyard Sunday School and Boys Club so he must have moved to the Richmond area before the start of the war.

Commemorating the war dead

Discussions about how the dead should be commemorated began the following year; three brass tablets had been put up by the families of Wilfrid Browne, Percy Kentrzinsky and Frank Lenzer, but there was felt a need for a general memorial to all who had been killed. The church deacons suggested the formation of a sub-committee and one was set up in July 1919. The Committee considered the idea of a stained glass window and the building of a hall on the disused graveyard at the rear of the church. In October progress on the various ideas was discussed at a church meeting; the costs for a window were high – from £100 to £125; this idea had been floated among some of the families concerned and 21 families promised £83. The idea of building a hall over the graveyard was deemed impractical.

Finally, on 10 November 1919, twelve months after the war had ended, a special meeting, attended by members of the church, the congregation and the Vineyard Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Association Brotherhood and chaired by the minister, Rev F W Aveling, considered various suggestions. A stained glass window, a lectern, a tessellated pavement in the vestibule and a memorial gift fund were mooted, but after much discussion, and a vote it was decided that:

- “A tablet should be erected in the church bearing the names of the men who had fallen in the war.

- A Roll of Honour on vellum should be inscribed of all those had left home to serve their King and Country

- A Fund should be raised to enable an Annual Memorial Gift to be given to a society connected with the church working among the young, or to individual young people who show promise in some particular direction and to whom a gift in kind, tuition etc would be an inducement to persevere”.

This suggestion was largely the idea of a Mr Bishop who was appointed to the War Memorial Committee which was then formed and which met very soon after on 16 November 1919 following the morning service. Mr Bailey was appointed as the Secretary of the Committee. A leaflet was printed appealing for donations and requesting that the names and details of those who had served in the war for inclusion on the Roll of Honour.

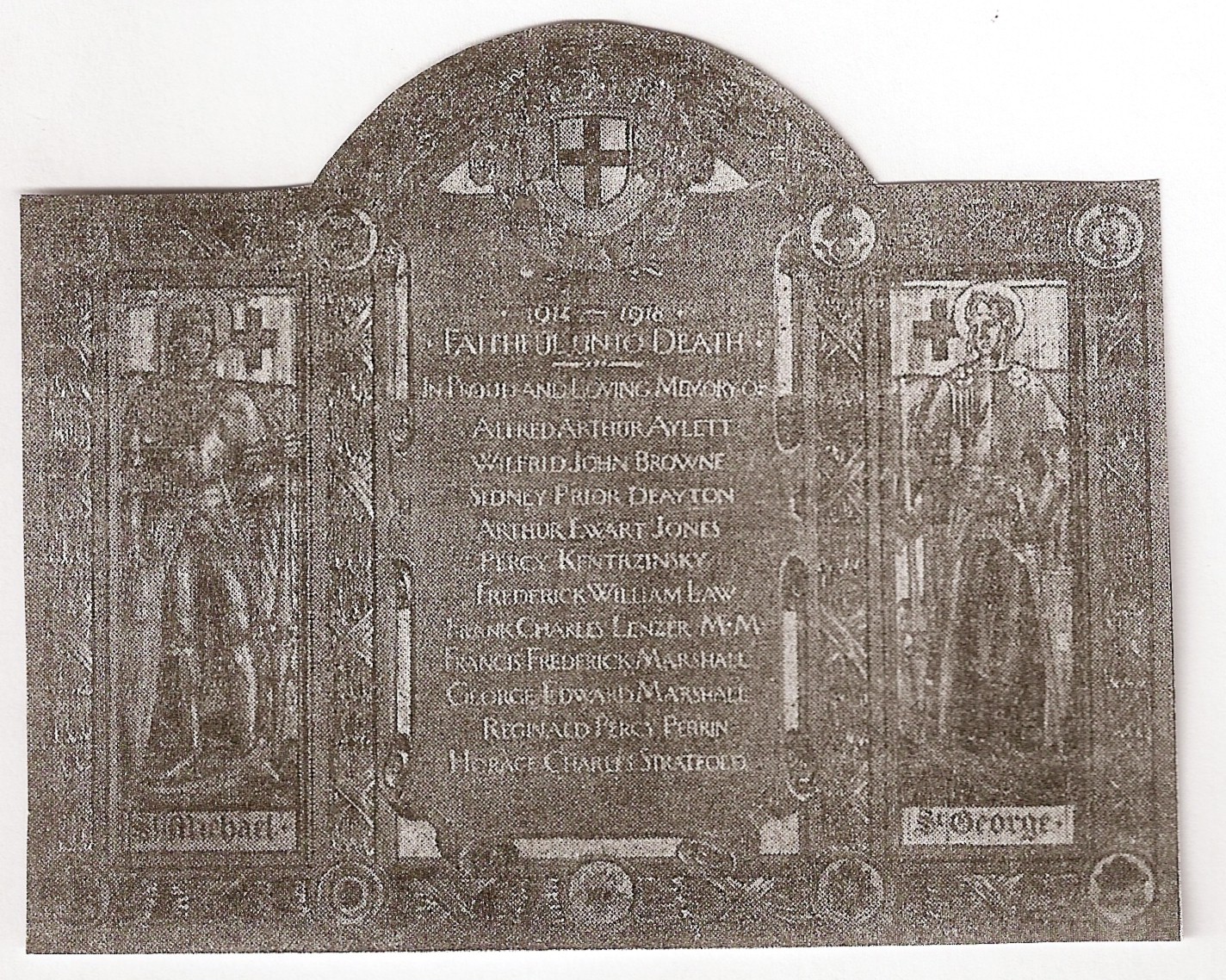

Memorial tablet

The Committee considered the type of material for the memorial tablet – alabaster, stone and marble being possibilities. However, Mr Bailey came with the idea of a tablet made from an oak panel painted in gesso relief. See ref 2 He suggested that the names should be carved in the centre of the tablet on a scroll. Bailey mentioned that he knew someone in the congregation capable of carrying out the carving. A young artist had also been recommended to him by a Mr H M Cundall. It is not clear whether Mr Cundall was a member of the congregation or merely an acquaintance of Bailey’s. The young artist in question was Charles Cundall, nephew to the older man. Born in Lancashire, Charles Cundall had worked as a designer for Pilkington’s Pottery Company and had studied at the Manchester School of Art before winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in 1912. He had served in the war and in 1918 returned to the Royal College before attending the Slade from 1919 to 1920. Now aged 30, he was living in Whitehead’s Grove, Chelsea. A painter, potter and stained glass artist, he was continuing his studies in Paris. See ref 3

Some of the Committee members went to the “South Kensington Museum” (see ref 4) to look at Italian gesso work as well as marble and alabaster tablets produced by a specialist company called Jones and Wills. However, it was decided that the memorial should be carved out of oak and in February 1920 Cundall was commissioned to undertake the design. The memorial was to have two panels depicting St George and St Michael which were to be painted by him using Italian gesso materials but with oils used to depict the nine regimental badges of those killed. As Cundall wrote to the Mr Bailey, the ‘two mediums combined give a very rich effect’. The carving itself was to be done by one of the congregation, a Mrs A Scales, whose husband was the church secretary. Her husband was on the Committee but left while the others made the decision as who should be commissioned for this work. Judging by the quality of her workmanship, she was an accomplished wood sculptress. She did not charge for her work. Another member of the congregation, Mrs Bowles, agreed to write and decorate the vellum scroll of honour. The wording on the memorial – “Pro patria 1914–18 Faithful unto death” was chosen.

Some disagreement between the Committee and Cundall arose. In June 1921 he wrote pointing out that the Committee’s resistance to some changes that he had suggested meant that the project had been delayed; it is also possible that there might have been a delay in getting the oak frame for the panel made. When Cundall undertook the commission he said that he felt he could carry it out fairly quickly and this was why he had agreed to a “very small amount” for his work. “You would not get any artist to carry out the design I intend to give you for less than £50 though I doubt you could for that” he wrote. He went on to point out that he realised that when he submitted the design that the estimate was “absurdly small” but he went along as it was for a good cause. He said that he was going to Paris and Rome for a year and would not be able to return to finish the work unless the Committee paid a more “reasonable” sum to make it worth his while. He estimated that he had spent a week on the design and had been to Richmond several times to see how “it was progressing”. He said he would not be able to start it in the autumn and it would take about two months to do it.

Bailey’s reply is not preserved, but Cundall finished his commission and was paid £43 for his work on 7 February 1922. The total raised from donations was £70 5s 8d which was somewhat short of the initial promises. After various items of expenditure, £5 16s 6d was left for the Memorial Fund. While church accounts have not survived from this period, ten years earlier the income for the church was £649 1s 3d so the amount raised for the Memorial Fund was quite substantial in comparison.

The memorial tablet was dedicated at a special service in February 1922 attended by the Mayor and other civic officials and church ministers. The memorial was moved from its original position some years ago and is now located on a wall of the balcony of the church. It was intended after the Second World War to add the names of Donald Brown and George Copper who had died in this conflict but for some reason this never happened. The vellum roll of honour disappeared at some stage in the years after 1922.

Annual Memorial Fund

The first meeting of the Governors (i.e. trustees) of the Fund was held in July 1921. There was £5 available for distribution. Two applications were considered; one from a Miss Whitman who was studying for a BSc degree at London University and the other from Miss Torrel who was studying at Carey Hall, Birmingham to go into the foreign mission field. Both were granted £2 10s 0d. It was decided that neither the names of the recipients, nor the amounts awarded, would be published. The following year it was then agreed to publicise the names of recipients and, in fact for the award to be given at a service “under the shadow of the memorial”.

Each year thereafter, apart from in 1940, grants were made to young people and presented at a service. During the Second World War the awards began to be presented on the Sunday nearest Remembrance Day. The awards presented ranged from books for those studying at college, and tools for apprentices, to fees for those studying for professional examinations. In 1982, the cost of books was so high that the amount in the fund was not able to sustain the granting of awards and in that year none were made. A fundraising event, such as a coffee morning, was suggested. In 1983 the amount available was £59.40 and awards recommenced. The following year another fund, the F C Wheeler Fund, was combined with the Memorial Fund to increase the value of awards and £64.34 was available. The last award was made in 1989 of £50 for books for Carol Baker, Assistant Brownie Guider, who wanted to take a Montersou [sic] course in childcare via the Open University. After this the Fund was incorporated into the church general fund as the amounts available had become so small.

Unlike those British troops today who are killed on active service overseas, the dead of World War I were buried or commemorated where they fell in battle. In Rupert Brooke’s words, ‘there is some corner of a foreign field that is forever England’’. See ref 5 In the case of those from the Vineyard Church their corner of England lay in Belgium, France, Turkey and Lebanon. The author has had the privilege of visiting some of their graves tended by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in northern France.

But a lasting memorial to the eleven men was the fund which helped a large number of the generations that followed them at the Vineyard to better themselves through education and training.

Appendix 1: LIST OF MEN WHO ENLISTED FROM THE VINEYARD CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH 1914

| SURNAME | INITIAL | RANK | UNIT | DATE |

| Allchen | L. | Asst Paymaster | Not known | Oct 1914 |

| Andrews | Pte | Not known | Oct 1914 | |

| Ashton | Pte | Not known | Oct 1914 | |

| Beechey | Pte | 6th Batt East Surrey | Oct 1914 | |

| Carter | Pte | 6th Batt East Surrey | Oct 1914 | |

| Chapman* | H.E | Pte | Surrey Yeomanry | Oct 1914 |

| Cracknell | L.J. | Pte | 6th (Cyclist) Batt Suffolk Regiment | Oct 1914 |

| Curbledon-Smith | A. | Pte | City of London Rough Riders Yeomanry | Oct 1914 |

| Dixon | Pte | 6th Batt East Surrey | Oct 1914 | |

| Drummish | Pte | RAMC | Oct 1914 | |

| Ewant-Jones | A | 2nd Lieutenant | 8th Batt.Welsh Regiment. | Oct 1914 |

| East | Pte | Not known | Oct 1914 | |

| Fox | H. | Pte | 6th Batt East Surrey | Oct 1914 |

| Frost | C.T. | Pte | 5th Batt East Surrey | Oct 1914 |

| Frost | J.R. | Sgt | 15th Hussars | Oct 1914 |

| Frost | W.J. | Sgt | 15th Hussars | Oct 1914 |

| Frost | Seaman | H.M.S. Garland | Oct 1914 | |

| Goldfinch | Pte | 1st Batt Middlesex | Oct 1914 | |

| Griffin | P. | Pte | 6th Batt East Surrey | Oct 1914 |

| Hatton | E. | Pte | Not known | Oct 1914 |

| Lucas* | A. | Seaman | Not known | Oct 1914 |

| Lucas | Gunner | Not known | Oct 1914 | |

| Parrish | Pte | 2nd Batt Royal Fusiliers | Oct 1914 | |

| Penfold | Pte | ? 2nd Batt Royal Fusiliers | Oct 1914 | |

| Perry | A. | Pte | Not known | Oct 1914 |

| Stevens | E. | Trooper | Not known | Oct 1914 |

| Tucker | J | Pte | Not known | Oct 1914 |

| Weston | Pte | Not known | Oct 1914 |

- * E Chapman and A Lucas have been identified as church members from church membership records; however, the Church Meeting minutes of 1 October 1914 state that of the 16 men who enlisted, five were church members. It is not known who the other three were.

Appendix 2: LIST OF MEN FROM THE VINEYARD CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH WHO WERE KILLED IN THE GREAT WAR

| SURNAME | INITIALS | RANK | UNIT | DIED |

| Aylett | A.A. | Pte | 1st Batt. Honourable Artillery Company. | 23/02/1917 |

| Browne | W.J. | Pte | Royal Army Medical Corps | 06/11/1917 |

| Deayton | S.P. | Pte | Princes Patricia’s Light Infantry | 02/06/1916 |

| Ewart Jones | A.

|

2nd Lieutenant | 8th Battalion.Welsh Regiment | 08/08/1915 |

| Kentrzinsky | P.W.D. | Rifleman | 1st/16th Batt. Queens Westminster Rifles | 01/02/1916 |

| Law | F.W. | Rifleman | 8th Batt. Post Office Rifles | 07/10/1916 |

| Lenzer M.M. | F.C. | Pte | 10th Cavalry Brigade Signal Company | 04/11/1918 |

| Marshall | F.F. | Rifleman | 16th Batt. London Regiment | 29/11/1917 |

| Marshall | G.E. | Pte | 4th Batt. Royal Fusiliers | 08/10/1918 |

| Perrin M.C. | R.P. | Captain | 7th Infantry Brigade | 27/05/1918 |

| Stratfold | H.C. | Gunner | 190th Brigade Royal Field Artillery | 08/09/1916 |

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the author’s friend, the late Christopher Portway (1923–2009), a resident of the Royal Hospital Chelsea. He served as a Lance Corporal in the Dorset Regiment from 1942 to 1946 and as a Territorial Captain in the Essex Regiment from 1947 to1987. He gave supportive advice as well as helped with some of the research needed.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank his friend Trevor Webster in his editing and proof reading of this article; also, Christopher Young for encouraging the author to investigate the Canadian War Veteran Records in connection with Sydney Deayton. Steve Newman, previously Regimental Adjutant of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, provided invaluable assistance also in providing information on Sydney Deayton’s last days on the Ypres Salient.

Sources

British Army Service Records 1914-1920 National Archives, Kew

Canadian Veterans Affairs Records website

Census Records 1881; 1891; 1901; 1911.

Private correspondence from Charles Cundall to the church 1921

Commonwealth War Graves Commission Records website

The London Gazette 10 October 1913, 18 September 1914 and 15 June 1915

Minute book of the Vineyard Congregational Church 1914-1924

Minute Book of the Memorial Fund Committee 1919-1921

Minute Book of the Vineyard Congregational Church Memorial Fund Governors 1921-1989

National Roll of Honour of the Great War: National Archives, Kew

Passenger Records: National Archives, Kew

Vineyard Congregational Church Manual 1911

Bibliography

Stephen K Newman With the Patricia’s In Flanders 1914–1918: Then & Now (ISBN: 9780968769607)

Colonel G W L Nicholson: Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War – Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (ISBN: 978-0773546172)

Note on author

Peter Flower has a B. Hons in modern history from London University and is an Associate of King’s College London.

References

[1] Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Association – for further information see Richmond History 29 (2008)

[2] Gesso is a permanent and brilliant white substance using gypsum and used for painting on wood.

[3] In the Second World War, Charles Cundall was an Official War Artist and in 1944 was elected to the Royal Academy. He died in 1971.

[4] Now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum

[5] “The Soldier” by Rupert Brooke, written in 1914