- This is an extended and updated version of an article “The Victorian burial ground of the Vineyard Chapel: from graveyard to garden” by Peter Flower, which originally appeared in Richmond History 37, published in 2016.

While building an extension[i] to the rear of the Vineyard Church in July 2004, a workmen’s mechanical digger broke through into unknown burial vault where five coffins lay. It was a vivid reminder of the original use of what is now a tranquil garden enjoyed by guests using the Community Centre, as a burial ground existed at the rear of the church for 40 years in the 19th century.

The church (or chapel[ii] as it was originally called), was built in 1830 on ¼ acre of land purchased in 1828 by the new congregation’s benefactor Sir Thomas Wilson.[iii] The plot was on open ground behind the houses on Hill Rise and the newly built Roman Catholic Church to the west.

At the rear of the new building a plot[iv] was set aside as a burial ground. This was the only burial ground outside the parish churchyard of St Mary Magdalene and the overflow burial ground opened 39 years before in what is now Vineyard Passage. The Vineyard Passage Burial Ground[v] (“Burial Passage”) was opened in 1791 by the Richmond Vestry with the first burial carried out the following year.

With the rapid population growth in the 19th century in London and other cities, churchyard cemeteries struggled to cope with the volume of burials, and where graves being dug on top of others, diseases could spread with shallow graves. A further concern was that of grave robbers. The Richmond Vestry offered a reward in 1823 of £50 for “the apprehension of those guilty of stealing or attempting to disinter any bodies in the Churchyard or Burial Ground with intent to steal the same”.

Before 1852 the only public burial places[vi] were generally in the grounds of Church of England churches. There was no similar cemetery in the grounds of St Elizabeth’s church next door. So the Vineyard Chapel’s small burial ground was unique.

The Vineyard Passage burial ground was full by April 1854, with around 400 burials having taken place over the preceding 63 years; no further bodies were allowed to be buried there except, for a further 20 years, some internments if vaults and brick graves were used for husbands, wives, parents and unmarried children of those already buried there.

To cope with the need for more burial space, Richmond’s Grove Road Cemetery was opened in 1839. With its rising population, Barnes Cemetery was opened in 1855, and Avenue Gardens Mortlake Catholic Cemetery in 1852.

For just 40 years the Vineyard’s small burial ground was used for church members. The last internment took place in 1870. The plot was small anyhow and was reduced in size[vii] by a third when the church building was extended a year later. Increasing church numbers and theneed to have choir stalls installed, resulted in an extension being built out into the burial ground[viii]. Although the building contractor was paid an extra £8 to remove the earth for the foundations[ix] there are no records that any graves were disturbed or moved at the time; presumably the graves and burial vaults were all located further away from the old building line.

Revd. Henry Beresford Martin’s coffin

Despite being used for 40 years, little is known about those buried in the graveyard. Thirty-seven names are recorded in the church records as having died during the period (Appendix 1) but only four of these are known to have been buried in the burial ground. Of these four there is only information about two of them. The first is the person whose coffin was found in 2004 and the second perso’s name appears on the only headstone which remains decipherable.

The coffin[x] belonged to the church’s first minister, the Rev. Henry Beresford Martin, who came from Warminster, Dorset (Appendix 2). He served a total of 10 years until his death in office in 1844 after a long illness lasting four years. His widow was Martha ,who was aged 35, and he left four young children. He had been married just nine years. At the time of his death the members of the church numbered about 60.[xi]

Appointed in November 1834, the church records state that “Mr Martin communicated the pleasing intelligence that he cordially accepts the invitation and intends to commence his probationary labours on the first Sabbath in the new year”. On 9 June 1835 Revd Martin was “solemnly set apart to the pastorate office over the church”.

It seems that the graveyard was either already in use or was likely to be so because on 3 March 1835 at a church meeting when the finances were discussed it was agreed that the “Minister, instead of having £100 guaranteed to him as a salary as for the past year should receive the product of the following sources: viz the regular contributions of the Friends and Subscribers (the quarterly collections for incidental expenses of course not included), any occasional donations from visitors and others, the proceeds of the burial ground (after deducting the necessary expenses of digging graves) and the balance of an Anniversary”.

No burial registers for the church have remained. It is likely that they were destroyed when the Church was burnt down during the “Great Fire of Richmond” in 1851[xii] as the church records stated that “nothing of any appreciable value was saved except the Pulpit Bible, many hymn books and few loose benches and a few other things not worth mentioning”.[xiii]

But what is known is that Revd Martin was buried in the graveyard. In his obituary in the Congregational Magazine it states: “His mortal remains were interred in the burial groundbehind his Chapel on Friday March 10th when the Revd Mess Richards of Wandsworth and Miller of Chiswick delivered the accustomed addresses in the Chapel and sat the grave. ‘He being dead yet speaketh’.”[xiv]

The workman who dug down into the hidden vault in 2004 found that the coffin nearest to the opening they made belonged to Revd Martin. They were not able to tell whether there was an underground entrance to the vault or whether it was merely bricked over once it was full, but in closing it up they ensured that Henry Martin and the others buried there rested in peace.

The last burial

Others recorded as being buried in the chapel grounds were Mrs Bradford in May 1845, Mr Gray in September and Joseph Steward Woodin in January 1870. Today, the only headstone surviving with an inscription that can be read is a family memorial to the Woodin family from Petersham (Appendix 3). Much of the inscription has faded due to weathering but what can be read lists Louisa Woodin and Martha Woodin. The latter was born on 6 December 1813 and died on 21 March 1817 aged three. Of course the burial ground was only open in 1830 so she must have been buried elsewhere. It is unclear who Louisa was but she may have been Joseph’s first wife.

Joseph Steward Woodin was interred on 8 January 1870 in the family vault.[xv] He was 83. According to a subsequent Minister of the Church, Revd Archibald Johnstone, Joseph was the last person to be buried in the graveyard.

The fate of the burial ground

So what happened to the burial ground after this? In a letter to the Church of 12 April 1854 from the Lord President of the Council an Order had been made directing that no new burial grounds could be opened in Richmond without the approval of the Government and for no further burials could take place in the burial ground of the Independent Chapel. This was as a result of the Act passed by Parliament in the previous session.[xvi] In the act, Richmond, among other boroughs like Staines, Chiswick, Merton and Mortlake was ordered to discontinue burials underneath the parish church and from August of that year to discontinue burials in the churchyard, in the parish burial ground (presumably the Vineyard Passage site) and in the burial ground of the Independent Chapel.

But we know of course that the burial ground was not closed at this stage as the last burialtook place in 1870. Whether the burial registers were given to the Commissioners is not known but appears unlikely from correspondence which took place in 1912 which is given below.

The Church received a general circular dated 1 March 1857[xvii] from Somerset House notifying them that the Commissioners had been required since 1837 to investigate the state of all Registers or Records of Births, baptisms, deaths or burials and marriages so these could be kept safe in fireproof rooms at Somerset House and provide legal evidence in any judicial matters. Many non-conformist congregations had such records and had passed these to the Commission. But not, it appeared, the Vineyard Chapel.

In a further letter dated 31 March 1857 the Church was asked about the “state, custody and authenticity’” of Non-Parochial Registers including Registers of Burials. The Commission had apparently received information that the Independent Chapel’s burial ground had been closed. They asked whether the Church wanted to “transmit” the registers to them for the “purpose of public utility”, stating that the burial ground was closed. Burials actually continued foranother 13 years. It is not known what the Church’s response was or whether any registers were sent but none are currently held in The National Archives.

The graveyard remained untouched for some years after the last burial. However, in 1902 the need for regular upkeep of the plot became apparent and arrangements were made to pay £2 10s per annum to the Church Officer cut the grass at least once a week during the summer.[xviii]

Ten years later, with the church membership at 150, the need for additional space led to plansto build on the burial ground site being considered by the minister, Revd Archibald Johnstone, and the church deacons. They were keen to explore the possibility of building a school room there for Sunday school classes. Revd Johnstone said, in a note to an unknown correspondent, that it was not possible to say how many graves the site contained as no registers could be found either at the church or at Somerset House. He thought there were about 20 tombstones and the last burial had taken place on 8 January 1870. He said that the level of the ground had been raised many years ago by about three feet. His view was that whatever human remains were left “must be at a considerable depth below the present surface”. The proposal, which would be put to the Borough Council, was not to disturb any of the remains. The foundations would not need to go down more than two feet to “secure a firm foundation”. A thick bed of concrete would be laid and between that and the floor of the new building a space would be left for air to circulate freely.

In November 1912, the Home Office wrote to Revd Johnston after receiving a letter from him. He was told they had no jurisdiction about putting buildings up on burial grounds; the writer presumed that the Disused Burial Grounds Act 1884, as amended by the Open Spaces Act 1887 should be considered. A Home Office licence would be required to remove any remains which might be found when digging the foundations and re-inter them in another burial ground; an advertisement would need to be published on three occasions giving notification about applying for a licence as well as individual notices given to any person known with a relative buried there. If tombstones and monuments were to be removed, then steps would need to be taken to comply with the Open Spaces Act.

The Church applied to the Council but was told in a reply on 5 March 1913 that the Highways Committee “could not see their way to entertain such proposal being of the opinion that a Burial Ground should not be built over”.

The graveyard remained untouched.

In July 1928, after the First World War, the Church made enquiries of the Congregational Union about the possibility of building on the graveyard again. The Secretary, Harold Shepherd, wrote back to state that the law prohibited building on graveyards unless a church or chapel was being extended. Even if this was the reason, the Home Office had to approve of the removal of bodies. The Ministry of Health in Whitehall also confirmed this in July 1928 that “it shall not be lawful to erect and buildings upon any disused burial ground except for the purpose of enlarging a church, chapel meeting house or other place of worship”.

And so the plans to build on the site were shelved – for good.

Two years later, in June 1930, the Council granted the Church a licence to erect a temporary shed on the site. No mention is made of the size or purpose of the shed and no other records exist about it.

The site remained untouched, with the headstones gradually falling over and the site becoming neglected.

In an interview[xix] with the author in 2001 one of the elderly members of the congregation, Marie Rumgay, remembered that as a child the gravestones were still standing before theSecond World War; she remembered large rectangular one in the middle of the site whichchildren used to play on. Her recollection was that this grave collapsed in the war. The church building was damaged towards the end of the war through a bomb blast which knocked out some of the windows. While not recorded, it is possible that some of the headstones were damaged by the same bomb blast.

What references exist in the Church Minute books in the post war period make mention of the “garden” rather than a graveyard and at some stage the remaining headstones were placed at the sides of the plot and the ground was grassed over

With the opening of the Vineyard Project drop-in run by Richmond Borough MIND in 1976, the site was used as a garden by those visiting and it continues to be used in this way to thepresent day.

Gravestones found in 2018

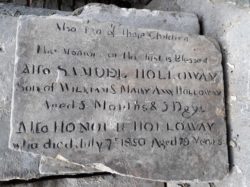

In August 2018, work was undertaken in the side alley leading to the garden to improve access into the building prior to step-free access improvements being made. In the course of taking up the paving stones, two were found to be old gravestones. They were put aside and later used as paving in the front of the building next to the porch.

One had been a large headstone, sadly now broken in half. Of the half that remained, the faint wording showed that it recorded the deaths of some members of the Holloway family. Samuel, the five month old child of William and Ann Holloway; in addition, the inscription recorded the death of Honour Holloway who died aged 79 on July 1850. A Mrs Holloway was the 33nd member of the church, joining in October 1833. Another Mrs Holloway joined on the same day and a subsequent note in the Church records mentioned that she died on 10 February 1851 after being ill for 36 hours dying in her 81st year (see Appendix 1). The relationship of these two elderly members of the same family is not clear.

The inscription on the other headstone is too weather-worn to read.

The garden is now a tranquil place to sit and chat with friends, or for quiet contemplation away from the bustle of the town centre.

Appendix 1: List of deaths of members of the congregation from 1830 to 1870

Listed in the Vineyard Chapel Books, Vol 1 1830 to 1857 and Vol 2 1857 to 1898

| Name | Date of death | Comments from the Chapel Book |

| Mr Way | 11.12.1844 | |

| Mr Bradford | ‘Died May 1845.’ | |

| Mrs Bradford | 20.05.1845 | ‘died on the 20th of May 1845 and was buried in chapel grounds’. |

| Mrs Mardward | 1847 | ‘Deceased.’ |

| Mrs Day | 25.03.1850 | ‘Departed this life on the 25th of March (1850) in the 84 year of her age; a ‘’shock fully ripe’’[xx]. |

| Mrs Mall | 10.06.1850 | ‘departed this life after painful and protracted sufferings June10 1850 age 57.’ |

| Mrs Robinson | 1850 | ‘departed this life’ |

| Mrs Stewby | 1850 | ‘departed this life.’ |

| Mrs Holloway | 10.02.1851 | ‘departed this life on 10th February 1851 after 36 hours of illness in her 81st year’ |

| Mrs Soden | 10.03.1851 | ‘departed this life on 10th March 1851’ |

| Mrs Byne | 11.00.1852 | ‘departed this life on the 11th of ’ |

| Mr Busby | 04.04.1852 | ‘departed this life on the 4th of March in the morning in a happy state of mind’ |

| Mrs Gardner | 16.03.1853 | ‘departed this life March 16th in peace’. |

| Mr Gray | 05.09.1854 | ‘departed this life on 5th September 1854; buried in the cemetery the 8th day of September 1854’ |

| Mrs Prance | 26.03.1855 | ‘died on 26th March after a membership of 12 years. |

| Mr Singleton | 01.02.1855 | ‘departed this life on first day of February 1855’. |

| Mrs Gray* | 1860 | ‘died’ |

| Miss Sale* | 1860 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Grandee | 1870 | ‘died’ |

| Mr Cox | 1865 | ‘died’ |

| Mr Cussell* | 1861 | ‘died’‘ |

| Mrs Cassey* | 1862 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Hannah* | 1857 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Steele* | 1867 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Ramsey* | 1862 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Fowles* | 1867 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Whitley* | 1868 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Hart* | 1863 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Bramley* | 1864 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Hewitt* | 1864 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Cussell* | 1862 | ‘died’ |

| Miss Emma Cox* | 1864 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Parker | 1861 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Laurie* | 1869 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Penteloon* | 1863 | ‘died’ |

| Mrs Youngman* | 1866 | ‘deceased’ |

*The names shown were crossed through by a later writer and are therefore not easy to read.

Appendix 2: Biographical Details: Rev. Henry Beresford Martin and his family

Census records

Henry Martin, born in 1810, married Louisa Peach (nee Buckler) on 17 June 1835 in Warminster a few days after he was inducted as Minister of the Vineyard Chapel. Louisa was from Warminster where Henry first met her. Their first son, John Buckler, was christened in Warminster in October 1836; presumably this was because of Louisa’s family connections there rather in their new church in Richmond.

In Richmond, at the time of the 1841 Census the family were living at 12 St John’s Grove, off Kew Foot Road, Richmond. Their children were John, aged 4, Eliza aged 2, Henry aged 1 and Charles 6 months.

When Henry Martin died, his widow Louisa and her children moved to Lambeth where the1851 Census records show she was living at 16, Brunswick Crescent with her son John and her daughter Eliza. There were three servants and two visitors staying. 10 years later, in 1861 shewas living at 7, Priory Grove, Lambeth and was recorded as being a “Freeholder”. Her other son, Henry, was living with her and was ‘Silk Maker’. Louisa in 1871 was 63 and then living n Hackney St John. Retreat Cottages where she lived was accommodation provided for the widows of Congregational Ministers and she was deemed to be an “annuitant” – a beneficiaryof the charity. Still there in 1881, she died in 1884 aged 76.

Extract from the Vineyard Chapel Book 1844

1844: ‘It is now the duty of the Officers of this Xtian Church to record the solemn truth that the hand which its proceedings have been these eight years past inscribed within this book is now cold in death – the Revd Henry B Martin the first pastor, after a short but happy pastorate, has been called to realise the blessedness of that heavenly state toward which he so zealously labored (sic) to direct the people of his charge. The following extract from the Congregational Magazine will supply particulars-

“Died on the 2nd March 1844 after a protracted affliction and in the 36th year of his age the Revd H.B. Martin, late pastor of the Independent church, Richmond, Surrey. Mr Martin was originally a member of the Independent church at Newton Abbott, Devon and subsequently of the churches at Silver Street, London and Warminster, Wilts. He was placed under the tutorship of the Revd John Raven of Hadleigh previously to his entering on ministerial labour. He became pastor at Richmond in the early part of 1835 and continued zealously and effectively to discharge the duties of his office, alas, for six years only – In the spring of 1841 he was seized with his fatal malady which almost entirely disqualified him for public labour.

“He was, however kindly and generously permitted by his affectionate people to hold the pastoral office till (sic) the day of his death and during the whole period of three years he was graciously assisted by various friends in the ministrations of the pulpit. He gradually sank into the arms of death. His faith was strong and unwavering. He was clam, tranquil and full of hope to the latest moment of his life. ‘His mortal remains were interred in the burial ground behind his Chapel on Friday March 10th when the Revd Mess Richards of Wandsworth and Miller of Chiswick delivered the accustomed addresses in the Chapel and sat the grave. ‘He being dead yet speaketh’.”

Appendix 3: Biographical details: Joseph Steward Woodin and his family

The 1841, 1851 and 1861 Census gives information on the Woodin family whose headstone stands in the Vineyard Church garden today. In the 1851 and 1861 they record that the family is living at Rutland Lodge in Petersham an impressive house still standing today in Petersham Road. It was built in 1660 for a Lord Mayor of London.

Joseph’s middle name was Steward, which was his mother’s maiden name. He was born in 1787. Joseph married Martha (nee Hamilton) in 1838 when he was 51 and she was 22. Her first child was a son (also called Joseph) born in 1839. The Electoral Registers for 1834 to 1842 show Joseph as being registered at 23 Marsham Street, Westminster but owning freehold property at Petersham.

In the 1861 Census Joseph Steward Woodin was listed as a “Proprietor of Houses”. Six children were living there, the eldest being his son Joseph Woodin who was 21. There were two servants. Martha died in 1854 aged 38 having had 9 children. Her last child, Frederick was born in that year so it is possible that she died in childbirth. But there is no record in the Church Book of her membership, or of her death or burial.

On the family headstone the first name given is that of Louisa. This is the only record for this name. Other names on the gravestone are Eliza Wooden who was 3 when she died in 1853 and a Martha Woodin who was a ward of Joseph’s.

When Joseph died he left “under £70,000” in his will – perhaps £6 million today[xxi].

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank his wife, Sandra, for her research into the Martin and Woodin families in the National Census Records.

Sources

Burial Act 1852 Chapter 85

- Electoral Registers 1834-1842

- National Census Returns 1841, 1851, 1861, 1871, and 1881 at The National Archives in Kew.

- Minute books of the Vineyard Congregational Church 1857-1898.

- Minute books of Deacons Meetings 1924-29

- Probate Record 1870

- The London Gazette 22 February 1870

- Vineyard Congregational Church Manual 1899.

- Various documents and letters in the Vineyard Church archives.

- Vineyard Congregational Church 150 Year Celebration booklet 1980.

Bibliography

- Tudor Jones, R. Congregationalism in England 1662-1962. (1962)

- Sellers, Ian Nineteenth Century Nonconformity (1997)

- Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. Briefing: Cemeteries, churchyards and burial grounds (2007)

The author

Peter Flower. B.A. Hons (History) and Associate of King’s College, London University. Peter is a member of the Vineyard Life Church and the archivist of the church records.

Notes

[i] The new block provided showers and toilets for the Vineyard Drop-in Centre. It was officially opened by Sir David Attenborough at a ceremony in 2004. His late wife, Sheila Sim, opened the Vineyard Project in 1977 and used to teach pottery there.

[ii] The chapel, with a gallery, was build facing north in Norman style, 50 feet by 35 feet, with vestry and schoolroom on one side, 12 feet wide. Rounded arches and mock slit windows reflected the Norman style of architecture. There were sliding shutters from the schoolroom into the chapel.

[iii] The building of the church and Sir Thomas Wilson’s involvement in this is detailed in Richmond History, the Journal of the Richmond Local History, No 23 (2002).

[iv] Nearly 70% of the land was set aside as the burial plot to the north of the church building.

[v] http://www.thevineyardrichmond.info

[vi] Burial Grounds (as distinct from parish churchyards) were started by non-conformists in the 17th century and more were established in the next century. It was not until 1819 that the first public cemetery independent of an Anglican parish church was opened at the Rosary Cemetery in Norwich which was pioneered by a non-conformist minister[vi]. The first public cemetery in London was established in 1827 in Kensal Green. Before the middle of the 19th century, cemeteries like this were generally run as commercial ventures, but after the passing of the Burial Acts from 1852 onwards urban churchyards began to be closed and municipal cemeteries came into widespread use.

[vii] The size of the burial ground was reduced to approximately half of the ¼ acre of the church plot.

[viii] The architect was a Mr Bennet. The work was carried out between June and October 1871 with Sunday services being held in the British School in the school rooms in the basement. Eight building tenders were received and the cheapest, from a Mr James, at £799 was accepted (Deacon’s Minute Book April 1871).

The extension, including space for a choir and an apse was approximately 36 feet long and is visible today by the different brickwork seen from the side ally. It reduced the size of the burial plot to approximately 620 square yards in total. As a result of the extension the insurance of the building was increased by £1000 to £3,800.

[ix] Mr James, the builder, was paid an extra £8 above his contract price to remove and cart away the earth from excavations from the grave yard. (Deacons Minute Book August 1871)

[x] There was an inscription in lead on the top of the coffin which identified the body as that of Revd Martin.

[xi] Vineyard Congregational Church 150 Year Celebration (1980)

[xii] Illustrated London News 23 August 1851.

[xiii] Vineyard Chapel Church Book 28 August 1851.

[xiv] Taken from Hebrews 11vs 4 (King James Authorised Version).

[xv] Vineyard Chapel Book 1857-1898.

[xvi] “An Act to amend the laws concerning the burial of the dead in England beyond the limits of the metropolis”.

[xvii] An Act of Parliament of 1840 required that these documents should be gathered together.

[xviii] Deacon’s Minute Book April 1902.

[xix] Interview held with Miss Marie Rumgay with the author in January 2001 based on notes taken at the time. Miss Rumgay was a member of the Vineyard Church from 1927, when she was aged two, until her death.

[xx] Taken from Job 5 vs.26: “Thou shalt come to thy grave in a ripe age, like as a shock of corn cometh in its season”. (King James Authorised Version).