Richmond and the Second World War: a book, a dramatisation and a podcast

To mark the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, The Museum of Richmond collaborated with the Society to mount an exhibition on Richmond’s experience of the Second World War. The exhibition ran from September 2015 to February 2016.

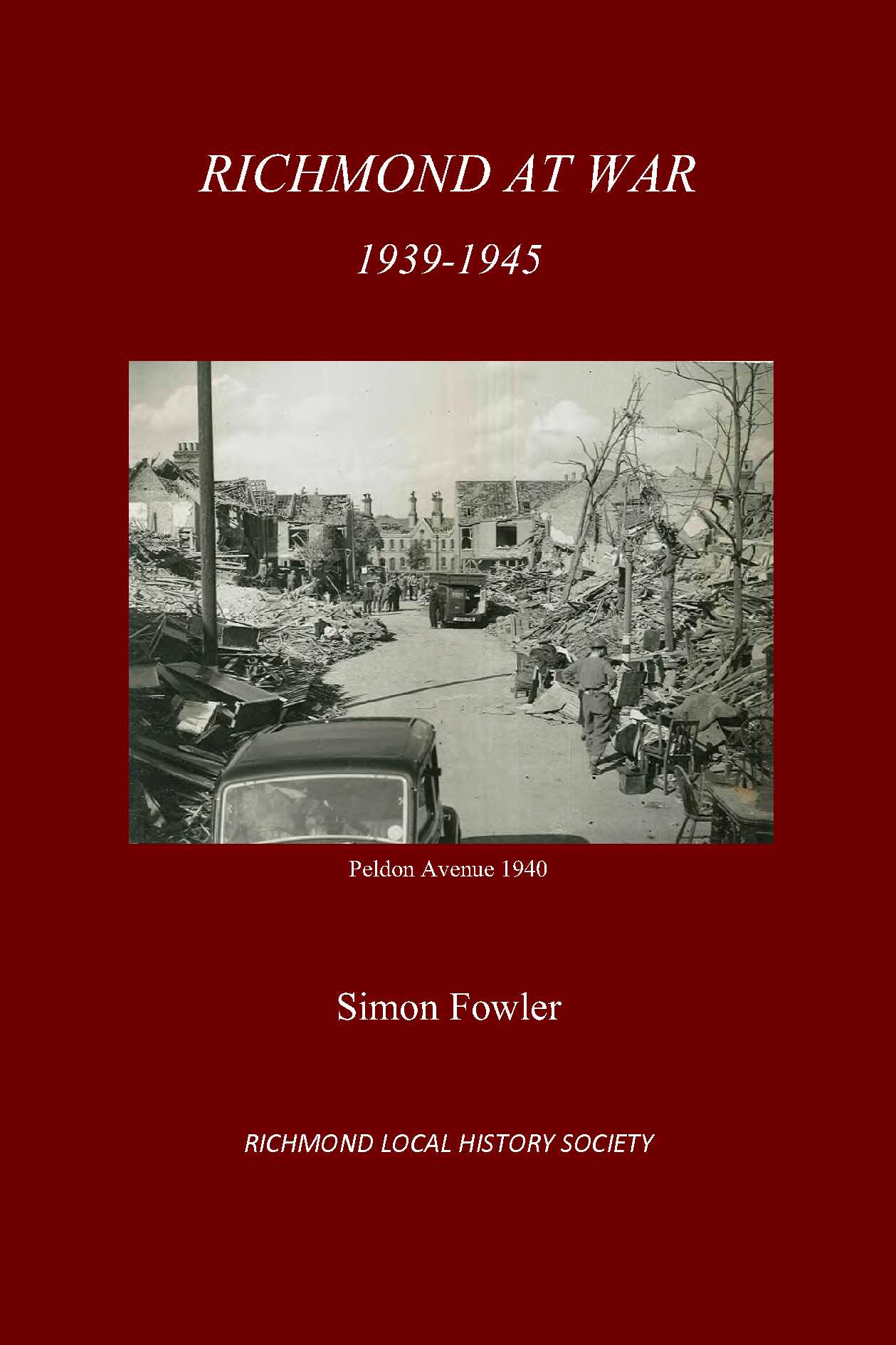

The accompanying book, Richmond at War 1939-1945, by Simon Fowler, published by the Richmond Local History Society in September 2015, tells the story of life in the town during the Second World War.

A series of raids saw the deaths of 98 civilians and damage to ten thousand buildings. The book also looks at some of the hush-hush activities in Richmond Park. There are stories of heroism, tragedy and good humour based on the memories of the men, women and children who were there.

A series of raids saw the deaths of 98 civilians and damage to ten thousand buildings. The book also looks at some of the hush-hush activities in Richmond Park. There are stories of heroism, tragedy and good humour based on the memories of the men, women and children who were there.

You can buy it at the Society’s meetings at £5 (non-members £6) or from our online bookshop. Our online prices include postage and packing.

Find out more and order a copy online

Back row: Christopher Hodges, Simon Fowler (author) and Joan Rundle. Front row: Liz Smith, Cat Lamin, Anne Hardwick, Michael Daly, Juliet Daly. Photograph by Alice Weleminsky-Smith

We’ve had lots of very positive comments about our event on 12 October 2015 with the Kew-based amateur theatre group Q2 Players, who did a wonderful job in bringing Simon Fowler’s book Richmond at War 1939-1945 to life.

Simon WROTE about the dramatised reading in an article, “All history is a stage”, in the Winter 2016 issue of Local History News, the magazine of the British Association for Local History.

See the cast list and a link to our Soundcloud page where you can listen to a podcast of the event.

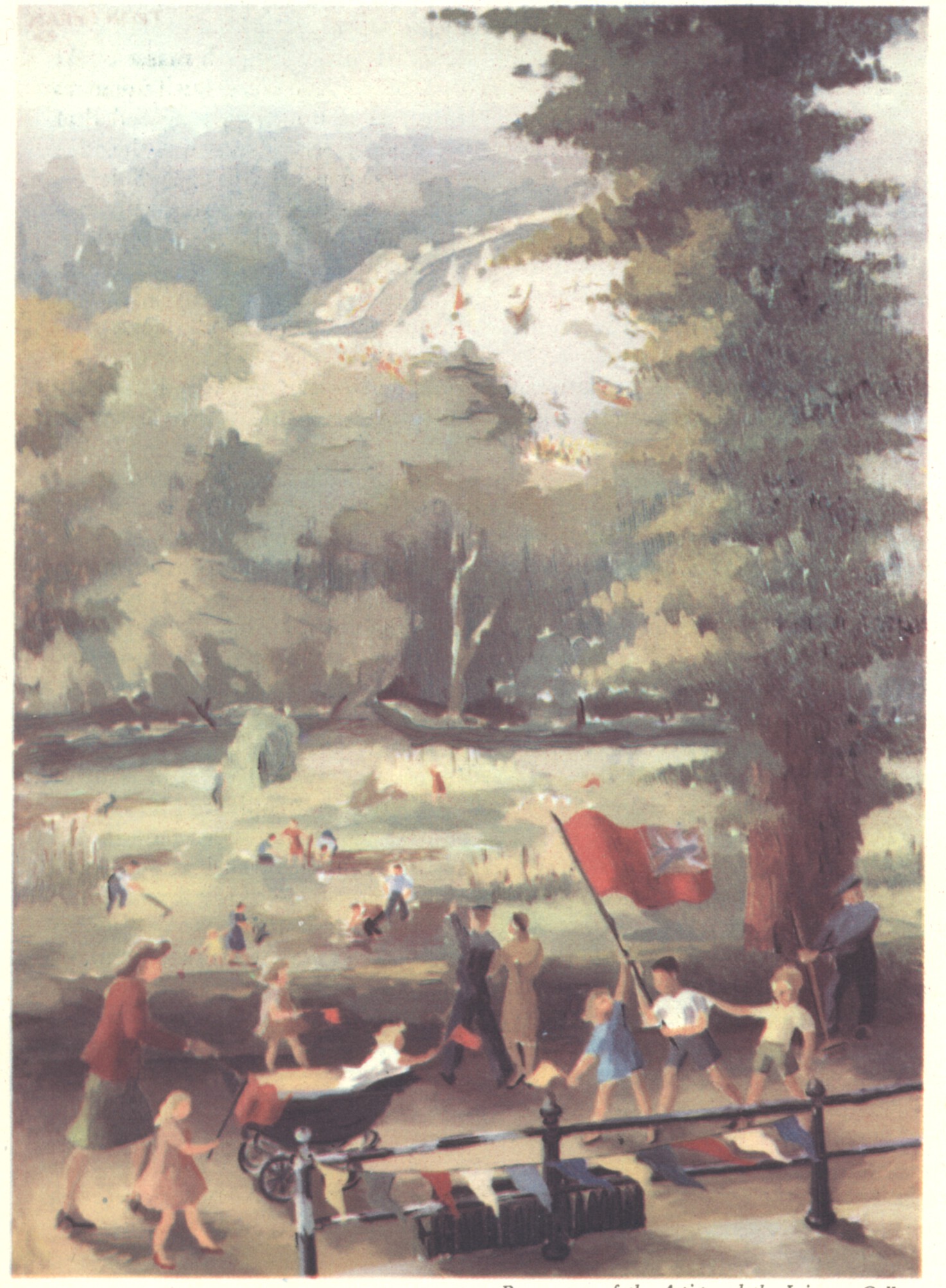

Victory Day Richmond 1945

The back cover of the book reproduces the painting ”Victory Day Richmond 1945”, by Richmond artist Mary Kent Harrison (nee Marryat); the painting was exhibited at The New English Art Club in 1945.

The back cover of the book reproduces the painting ”Victory Day Richmond 1945”, by Richmond artist Mary Kent Harrison (nee Marryat); the painting was exhibited at The New English Art Club in 1945.

Her youngest son Stephen, who has set up a set up a website to record his mother’s work, says it was painted from the balcony at 1 The Terrace in Richmond, where Mary and her parents lived during the war years.

Gathering local memories

The first edition of our publication Kew at War invited readers to send in their own memories of the Second World War. There was a good response. Some were added to our second (2013) and third (2016) editions which contained, for instance, a splendid account of the youth club going out to raise money, led by the vicar playing his trumpet, and a tribute to the work of the RAF and WAAF clearing up bomb damage in 1945. There are also reports, and references to new research, on where the bombs fell.

Some of the new material was also used in Richmond at War 1939-45 by Simon Fowler, a companion volume to the Society’s other publications on Kew and Ham during the Second World War. Simon co-ordinated the Society’s Second World War project, which included an exhibition at the Museum of Richmond and, for the Richmond Local History Society, a dramatised reading of people’s experiences of living in Richmond during the war.

Another Society member, Alette Anderson, gathered the memories of elderly residents who remember living in the town during the War. Her interviews have been used in the book and the tapes themselves have been deposited at the Museum of Richmond for everybody to enjoy.

We have also been receiving the occasional memoir including a delightful account of the activities of the Naval Cadet Corps in the borough. The young Cadets did their bit for the war effort before joining the Navy.

The ravaging of Richmond

Richmond eighty years ago was already a London suburb, although quite a lot of light infantry was stationed there.

Between 9 September 1940, when high explosives bombs fell on Mount Ararat Road, and March 1945 when one of the last V2 rockets exploded in Richmond Park, the town suffered over 450 separate bombing incidents, most of them in the winter of 1940/41.

In addition, 602 high explosive bombs, landmines, and other devices were dropped on the town.

Nearly 100 local people were killed, 397 were badly injured and 762 were made homeless.

The worst single incident occurred on 20 September 1940 when landmines were dropped on Peldon Avenue (now Peldon Court, Sheen Road) and Courtlands. All 49 houses in Peldon Avenue were completely destroyed.

Two months later, on 29 November, hundreds of incendiaries were dropped on the town centre. The Town Hall caught fire and the Public Library was severely damaged.

There was a direct hit on the British Legion Poppy Factory in Petersham Road, which had a large communal shelter. Eight of the occupants, all wives and children of ex-servicemen, were killed. All in all 27 people were killed that night.

Richmond’s refugee crisis

Eighty years ago, on 12 September 1940, hundreds of refugees from the East End arrived at short notice in Richmond. They did not receive a warm welcome. Find out more.

Lend your mite for Britain’s might

A highlight of the Second World War years were the war savings weeks in which towns and cities vied to raise money to support the war effort. In two weeks in February 1941 and April 1942 nearly £900,000 was raised in Richmond alone.

A highlight of the Second World War years were the war savings weeks in which towns and cities vied to raise money to support the war effort. In two weeks in February 1941 and April 1942 nearly £900,000 was raised in Richmond alone.

Using the pre-war network of savings committees, people were encouraged to buy interest-bearing bonds and certificates to help fund the war. In 1942 National War Bonds earned 2.5 per cent interest and Savings Certificates 3 per cent to be redeemed after the War. As well as raising welcome money, war savings weeks had the additional value of reminding citizens why they were fighting the war.

Two scrapbooks at Richmond Local Studies Library show how the Weeks were organised locally. The 1941 War Weapons Week took place between 29 March and 5 April. A target of £250,000 was set, although £368,625 was raised mainly though the purchase of War Bonds. This is roughly £16m today.

For most residents the highlights were probably the War Weapons Exhibition at Wright Brothers shop in George Street, where visitors could enjoy a “ride in a Power Driven Gun Turret of a modern heavy bomber.” And some 6,000 people went round the Royal Navy patrol vessel Sarah Munro, which was moored at Richmond Pier.

The week began with a luncheon addressed by a junior minister Chuter Ede, and ended with a ball at the Castle Ballroom with music provided by the Band of the RAF.

Ten months later, between 7 and 14 February, saw Warship Week, with the slogan “Signal to Save”. The town was set the challenge to raise £250,000 to build and fit out a sister ship to HMS Richmond. In the end the Week made £458,050 (£18.25m today). The Week was launched by the writer and humourist A P Herbert, who lived on Chiswick Mall, and was then serving in the Auxiliary Navy on the Thames.

And a successful Week concluded with a grand dance at the Castle Ballroom with Harry Roy and his Band. Roy was one of the top bandleaders of the period. Tickets cost a guinea, which included a 15 shillings savings certificate. The event was organised by the local Round Table who promised that revellers “are assured of a cheerful, and what we think you will find original, evening”. On the wall above the orchestra was a full-length portrait of Nelson with huge flags draped on other side of it.

Another star was children’s presenter Uncle Mac (Derek McCulloch) who came to a children’s matinee at the Royalty Kinema, attended by 1200 excitable young people, to judge essay and drawing competitions.

Again there was an exhibition showing war materials. A local paper reported that “A domestic note was introduced in one photograph which showed a Lieutenant knitting a pair of socks”. But despite a working model of a destroyer, submarine periscope, bells of HMS Chester and a German mine, the exhibition was not popular and questions were asked whether it had been worth the time and trouble taken to organise it.

However, the Weeks undoubtedly made an impact and their success showed the commitment of local people to the war effort.

Richmond’s Dad’s Army

Members of No 2 Platoon, who were based in Richmond, assemble on Richmond Green before going to Bisley for a shooting match

Records at Richmond Local Studies Library tell the story of Richmond’s http://premier-pharmacy.com/product-category/asthma/ Home Guard – or, to be formal, the 63rd Surrey (Richmond) Battalion, Home Guard. Its members guarded importance installations across Richmond, Kew, Ham and Petersham for almost four years. It also had an important and now largely forgotten role in training young conscripts before they joined the Army. And had the Nazis landed, the Home Guard would have been expected to defend the town against the invaders.

Some 800 local men responded to the radio appeal of 14 May 1940 for men to enlist as Local Defence Volunteers. Most were veterans of the First World War, and even the Boer War, who were too old to join up but not old enough to fight.

In the words of their commander, Lt Col AE Redfern, they were all “very much out-of-date, a bit short in the wind, and very rusty [but this was compensated] by their enthusiasm and eagerness to get going.”

Companies were set up in Richmond, Ham and Petersham, and Kew, with special platoons in Kew Gardens, Richmond Park and at the Chrysler Works (where the Kew Retail Park is today).

It could be an irksome duty, because men were expected to drill and patrol often after a long day’s work and to give up their weekends for training exercises.

The Chrysler Factory Detachment of the Home Guard’s Women’s Auxiliary Service on parade. The Chrysler Factory was on the site of what is now Kew Retail Park

There was also a Woman’s Auxiliary – known as the Wassies – with 120 members who provided first aid, clerical help, signalling, transport and, most appreciated by the men, a canteen “and what’s more they washed up after we had eaten.”

Initially both uniforms and weapons were in short supply. One platoon patrolled with sticks loaded with lead shot made by the employees of the Poppy Factory.

During the Blitz the Home Guard protected bridges against possible German attack and also guarded houses where live bombs were suspected of being present.

With Allied victory increasingly likely, the Home Guard nationally was stood down on 1 November 1944. The battalion marched for the last time through the town a few days later in pouring rain to a rally at the Richmond Theatre.

Many of the men had enjoyed themselves so much that in 1946 they opened a social club at Lansdowne House on Petersham Road to reminisce about old times.Sadly it did not last long, although a similar social club in Barnes still thrives.

Coping with the Blitz in Richmond

How would you have reacted to the Blitz? It’s not something, thank goodness, that many of us have gone through.

Richmond Local Studies Library has the diary of a young woman, May Lawrence, who lived through the Blitz in the town. Her experiences make graphic reading.

Miss Lawrence lived with her parents just off the Lower Mortlake Road. She was a clerk with Richmond council.

Nearly 100 civilians were killed in the town during the Blitz which was at its worst locally in October 1940.

On 1 October she: “woke up to an awful whistling noise as if something was rushing through the air, then a dreadful bang which lifted us from our bunks [in the shelter in their garden]. We shouted we are hit the house will be gone. Anyway after noting our house had not been hit, we managed to sleep a little.” The noise came from a blast that destroyed St Paul’s Church Hall in Stanmore Gardens and damaged the houses opposite (now Finucane Court). “We saw Mr and Mrs James whose house is all holes and windows out. She looks terribly white and so does Mr James.”

On the 17th at “7pm Jerry was overhead again. It was a dreadful night. One bomb came down at 11 it was a screamer, terrific thing, and fell on Park Road No 1. There was another huge bang at 6 this morning.”

And on the 24th: “We had two raids today. This afternoon we heard machine gunning and George [a work colleague] and I ran below for shelter. I never ran so much in all my life… “

A few days later the windows in their house were blown in. It took a week for replacement glass to arrive.

Her father was a handyman and took considerable trouble to make the shelter in their garden as homely as possible. On October 12th she writes that “Dad has put a door on our shelter and we have the curtains on rings now and it is very good.” A few days later he papers the whole shelter.

But occasionally they saw the RAF take on the Luftwaffe. She was at Langholm Lodge at lunchtime on the 9th. “We saw Jerry being fired at from the river bank and… I raced to the water’s edge and followed Jerry as they were firing. Then we saw three Spitfires after him flying low. The first one fell out injured unfortunately. Then the other two raced after Jerry and went after him into a cloud.”

Several entries showed how scared she was. On the 29th, she confides to her diary that “all our nerves very bad indeed. We hear that they are changing the [anti-aircraft] guns to further out as we have had such a bad time. I hope this is true for I do not know how much longer we are going to stand up to it.”

Fortunately May survived the Blitz and, indeed, the war.

Discovering more about Richmond’s war casualties

Richmond suffered its fair share of casualties during the Second World War. Just under a hundred local civilians died, mainly during the air raids in the autumn of 1940 and during the V1 attacks in the summer of 1944. And several hundred local servicemen failed to return home.

The Richmond at War Project would like to know more about these men and women. Basic information is recorded on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website at www.cwgc.org. But what more can we find out?

We only know a lot about just one casualty: Battle of Britain ace Paddy Finucane who was shot down over the English Channel, aged just 21, on 15 July 1942. His parents lived in Castlegate. He is remembered today in Finucane House on the corner of Lower Mortlake Road and Raleigh Road.

Surely other local men and women deserve to be better known too. Men like Warrant Officer Geoffrey Hickman of 92 Squadron RAF. Having escaped from a prisoner of war camp, he spent a year on the run in occupied Poland before being murdered by the Gestapo in Warsaw. Even the War Graves people don’t know the exact date of his death, except that it was in the last ten days of 1943.

Richmond’s own Spitfire

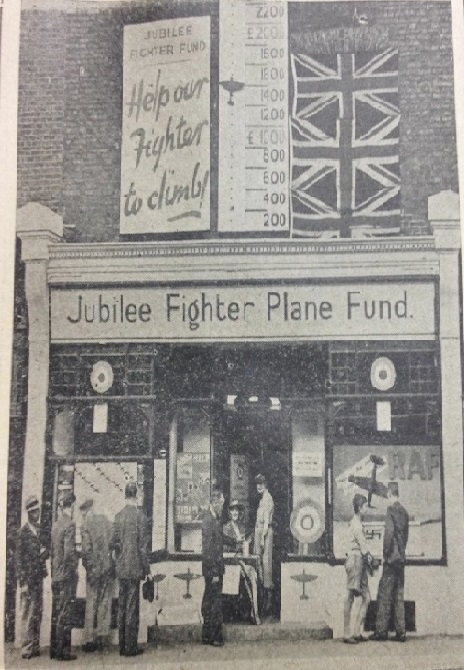

At the beginning of the Blitz in August and September 1940 thousands of people in Richmond clubbed together to buy a Spitfire for the Royal Air Force. It was a show of defiance against the seemingly all-powerful Nazi war machine.

Richmond was one of dozens of towns and cities that bought machines for the RAF. A volume of press cuttings at Richmond’s Local Studies Library reveals how they went about raising the £5,000 required. This is roughly equivalent to £275,000 in today’s money.

The plane soon became known as Jubilee, celebrating the Golden Jubilee of Richmond becoming a borough.

As the campaign developed almost every society, club and pub in the borough was involved raising money from members and the general public. Boatmen on the river offered one day’s takings to the Fund which amounted to £59.

Among the ideas floated were dances, garden parties and street performances by children. Small bracelets made from the bullet-proof windscreens of crashed Spitfires were sold for two shillings each. Nasty Crash clubs were set up, with members promising to subscribe a penny or two for every enemy aircraft brought down during September. Lists of donors were published in the papers. The Mayor headed the list with £100. And a tramp walked into one of the special shops and offered three-farthings to the staff telling the shop worker: “This is all I have got”.

There was a big collection box at Lion House in Red Lion Street bearing a model of a fighter plane. Two shops selling bric-a-brac in aid of the Fund were opened in George Street and on Hill Street, opposite the Town Hall, which “no one could miss seeing it as it bears the name of the Fund in the national colours, has fighter planes painted on a side wall and contains air raid relics in the window”.

Undoubtedly the highlight of the campaign was the arrival of two Dornier bombers which were displayed on Little Green. The first was in 400 pieces, so leaving something to the imagination. It was joined a few days later by a Dornier 17 that had crashed after bombing Buckingham Palace. Visitors paid a penny or two to inspect the planes.

By the end of September constant raids and air raid warnings began to affect fundraising. The papers reported that “prevailing circumstances have somewhat hampered the efforts of the organisers”.

Yet the very public arrival of the war over Richmond in mid-September led to a surge in support. Well over half the money raised came in the last two weeks of the campaign. All in all just over £6250 was raised with the surplus being given to the RAF Benevolent Fund.

Unfortunately Jubilee had a rather undistinguished career. To the RAF she was Spitfire Mk IIIB no. P8347. From 1941 she served with 222 Squadron engaged in fighter sweeps across northern France. Within a few months, however, she was mothballed as newer marks of Spitfires were introduced.

The postmen who never came back from the War

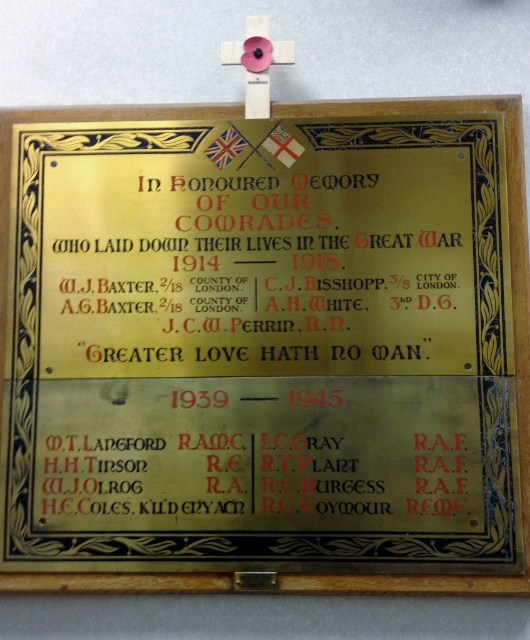

The next time you collect a parcel from Richmond Sorting Office glance at the brass plaque listing the local posties who gave their all during the two world wars.

The next time you collect a parcel from Richmond Sorting Office glance at the brass plaque listing the local posties who gave their all during the two world wars.

Unusually for a war memorial there are more names from the Second World War. The stories of the men in many ways tell the story of the War from a British perspective.

Henry Ernest Coles is the only civilian casualty. He was killed on 10 July 1944 when his house in Palmerston Road, East Sheen suffered a direct hit from a V1. At 53 he was too old to serve in the forces so had joined the Home Guard.

Signalman Herbert Henry Tinson died as a Japanese prisoner of war on 30 June 1943. He was actually a member of the Royal Signals Corps, not the Royal Engineers as given on the memorial. Undoubtedly he was taken prisoner during the Fall of Singapore in February 1942.

36-year-old Lance Sergeant William Olrog, Royal Artillery, was killed on St Valentine’s Day 1942 during the last chaotic hours before the British forces surrendered to the Japanese.

Walter Thomas Langford, a postman driver, served in the Royal Army Service Corps and died on 2 April 1943, aged 39. Walter (pictured here) was the son of Walter and Alice Langford of Richmond, and was the husband of Dorothy Gladys Langford, of Richmond. He is buried in Bengazi War Cemetery near Tripoli.

The last months of the War saw the death of Craftsman Ronald Goymour REME on 5 February 1945. He is buried at Leopoldsburg war cemetery. He may have died of wounds at a military hospital which was established in the village in late 1944.

Three former postmen died while flying on missions with Bomber Command over Europe.

Sergeant Les Gray, who came from Hounslow, was killed on 9 June 1942. He has no known resting place and so is commemorated at the Memorial at Runnymede. Aged 21, he is the youngest person on the memorial.

Wireless Operator Robert Plant died a few days later on 26 June. He is buried at Wouwaart Churchyard near Leuven in Belgium.

Sergeant Roy Burgess was a navigator in 106 Squadron. He was killed on 9 October 1943 and lies in Hanover War Cemetery. Roy was the son of Richmond residents Walter Ernest and Ellen Elizabeth Burgess of Richmond.