Conor Mark Jameson (pictured, left) gave a talk on W H Hudson to our Society in September 2022. In this extract adapted from his biography of Hudson, published in 2023, he describes a long-forgotten campaign to save Kew from the threat of development.

Reading the latest list of supporters of the Society for the Protection of Birds (SPB, before it became Royal), Hudson noticed that an old soldier he knew and often chatted to, who stood guard at the Queen’s Cottage grounds, had just signed up with the Society’s local branch. Hudson knew the man was a lover of birds – “especially of robins”.

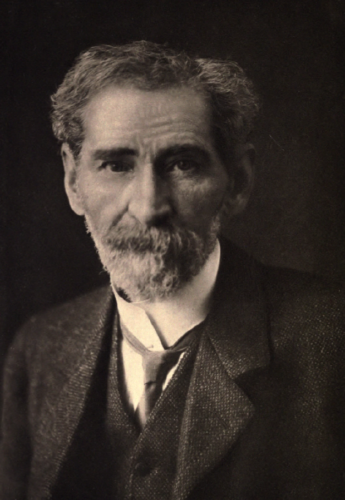

William Henry Hudson (1841–1922) was an Anglo-Argentine author, naturalist and ornithologist.

W H Hudson occupies a special place in the history of Richmond. He was a prominent campaigner in stopping the building of the National Physical Laboratory at Kew at the turn of the 20th century, as well as being a campaigner more broadly on protecting the wildlife of London’s parks and green spaces.

His last book, A Hind in Richmond Park, was completed by a friend soon after Hudson’s death.

When these Cottage Grounds at Kew were gifted by Queen Victoria to the people to mark her 1897 Diamond Jubilee, and opened to the public the following year, Hudson wrote to The Times in April 1898 to urge that access be channelled in a way that maintained the value of the site for wildlife. He also underlined Kew Gardens’ importance as a sanctuary for the people, calling it “a boon to London visitors, the tired workers with hands or brain in search of refreshment for body or mind”.

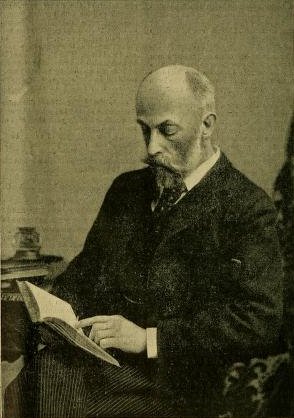

Hudson’s suggestion was duly adopted. Aretas Akers-Douglas who, as the First Commissioner for Public Works and Buildings, was the government minister responsible for Kew Gardens, attended Parliament to assure the House and the nation that Kew would remain “a great sanctuary of all the wild bird life in the district’. You can sense Hudson’s satisfaction when he subsequently writes, after a visit there with his close friend and Kew resident Emma Hubbard in spring 1899, that it now “seems a wider, more refreshing place than ever, with crested grebes and coots at home, the shade of oaks from the sun, and the greenness of leaf and grass and fern”.

Aretas Akers-Douglas, the government’s First Commissioner for Public Works and Buildings from 1985 to 1902, who was the government minister responsible for Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens was a safe haven for nature and nature lovers in the context of the landscape beyond, in which birds faced such relentless and unbridled persecution. The SPB, at its latest meeting, resolved to write to the Home Secretary requesting that flagrant crimes against rare birds be properly prosecuted, in light of the shooting of three or four ospreys just arrived from Africa at their breeding grounds in Scotland. “This last scoundrely act will probably see out this species as a member of the British avi-fauna”, Hudson seethed. Kew, by contrast, seemed secure. Passing migratory ospreys would even sometimes be seen fishing at the nearby Pen Ponds in Richmond Park, out of range of the rural guns.

But danger loomed. The first trace of Hudson’s concern about threats to Kew Gardens was evident in November 1897 when Hubbard relayed the news to him that trees had been felled there. Few things triggered Hudson like the removal of what trees survived in the rapidly expanding and congesting metropolis.

Plans to build the National Physical Laboratory at Kew

Early in 1900, the unthinkable happened: the government made its first announcement of an intention to build the National Physical Laboratory in the grounds of Kew Gardens. An agitated Hudson was soon writing again to The Times again, on 14 April, about this “great and disagreeable surprise to the inhabitants of London”. He was quick to remind readers of Her Majesty’s expressed wish when she gifted the land to her people: “The Queen earnestly trusts that this unique spot may be preserved in its present beautiful and natural conditions” had been the pledge.

Rising Liberal statesman Sir Edward Grey got involved, perhaps at Hudson’s bidding, writing to Emma Hubbard that same month. She shared Grey’s letter, and Hudson thought it encouraging. A suggestion was then made, possibly by Grey, that a copy of Hudson’s letter to The Times might be sent to every Member of Parliament. Hudson thought the cost would be prohibitive, running to £5 for postage alone. He proposed instead to print a limited number targeted at MPs “who may be supposed to take an interest in such things”. And he urged that it be reproduced verbatim. He had been advised (perhaps by Grey) to remove a passage containing what Hudson called a “damning fact” that showed what government was capable of if the public didn’t protest. Hudson saw no reason for such caution. “I know my facts are right, and the ‘Works’ know that too”, he vowed.

It seems likely that the damning fact was Hudson’s reference to the cutting down of 700 elm trees in Regent’s Park in 1880, which, when he witnessed it, had caused him so much trauma. These same trees I believe were the place he found by chance on his first rovings in London in the days after his arrival from South America to live in London, and which I think so impressed his fresh, visitor’s senses, with their huge rookery in full cry. It had thrown a kind of comfort blanket over him in this strange new place. He never got over returning there for solace, and finding it torn down.

Raising the issue with MPs

At the end of April Hudson reported to Eliza Phillips of the SPB that the residents of Kew were now agitating against the development, which would affect four acres. They were now taking the initiative and carrying the cost of reprinting his Times letter and sending it to all Members of Parliament. She asked him about the feasibility of compiling the MPs’ home addresses, and he pointed out that this would be tricky as many of them used temporary accommodation – hotels and hired houses – while attending Parliament. On May Day 1900 she re-typed his Times letter while Hudson collected signatures for the petition.

While this local upwelling of resistance was welcome, with its input of resources, Hudson recognised that the protest must come from a wider constituency. The matter concerned all Londoners, after all, and more of them must therefore raise it with their MPs. On 10 May, SPB leader Etta Lemon offered to help send out more copies of the letter, so Hudson dropped 18 of them at the Bird Society offices for her to distribute to “persons of importance”.

Margaretta (“Etta”) Lemon, a founding member and the first honorary secretary of what is now the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Image from Surrey History Centre

Hudson received a letter on 8 May from Lord Balcarres, who was to ask the question in Parliament. From what he reports, Hudson may have been in the public gallery to witness the matter being raised. He later reported that, when questioned on the proposals, Akers-Douglas (who would become Home Secretary in 1902) on behalf of the Conservative government had “assumed an aggressive air”, and then claimed that “exaggerated statements had been made in the press”. Hudson knew that this could only have been in reference to his letter, as no other newspapers had covered the issue. “If I had not written the letter the original plan would have been carried out”, he assured Lemon, pointing out that Kew Director Sir William Thiselton-Dyer’s protest had been ignored.

An alternative plan – building in Old Deer Park

Proponents of the development, recognising the mounting strength of feeling against it, now revealed their alternative plan, perhaps hoping that it would look benign by comparison, and wrong-foot their opponents. They were now proposing to build on the Old Deer Park nearby instead of the site alongside the Queen’s Cottage Grounds.

While this might be good news for the Grounds, it had simply shifted the problem and threat to the Old Deer Park. This prompted an intervention from the famous novelist Ouida (Maria Louise Ramé), who wrote in protest to the Westminster Gazette, with other letter-writers responding in turn.

The novelist Ouida (Maria Louise Ramé (1839–1908), photographed in 1874

Hudson wrote to Emma Hubbard immediately after a committee meeting of the SPB in June, at which the Old Deer Park threat had been discussed. A coalition of bodies including the Commons Preservation Society and the Selborne Society had now resolved to take the matter to the House.

Hudson escaped from London to the New Forest, in precarious health, but he remained preoccupied with the Kew campaign, even while out of town. Etta Lemon wrote to him there, about a proposed deputation to Parliament. He shared the news with Emma Hubbard. “Mrs Lemon asks me to represent the Society – a joke on her part, I suppose.” Nothing could have terrified him more.

Hudson is overcome by social anxiety

Hubbard tried to cajole him into finding the nerve to overcome his social anxiety. A rare surviving letter to his wife Emily is revealing, as he now turned to her for moral support, she perhaps understanding his phobia better than anyone. He was under pressure from all sides from those who wanted him to lead the charge. He must have felt cornered, and in a quiet room somewhere in the Forest he wielded his pen in self-defence. “I have a bundle of letters saying no to write – Mrs Hubbard, Lemon, Chubb, Lord Balcarres!” He was almost in fear of his life. “I suppose this everlasting worry about my ‘saying a few words’ in public will only end with the silence that comes on a man once and for all,” he pleaded.

For all his passion for this cause, Hudson was now in the grip of dread that only sufferers of social anxiety might fully understand. He made no attempt to disguise it. He wrote again from his bolthole in the New Forest, this time to Eliza Phillips on 19 June about his “hopeless weakness” and “helplessness”, pleading that they instead ask Sir Edward Grey to represent the SPB, in his role as a Vice-President.

Of course, in the end Hudson didn’t have to lead or be spokesperson for the delegation, and it is curious that, knowing him well by this stage, all his peers would still try to push him forward.

He continued to “strategise” while away and wrote to Hubbard from Hampshire at the end of June, suggesting how they might take their protest to the Treasury. He says he doesn’t know anyone with sufficient clout to influence that key part of government and reminds Hubbard that she is much better connected. Ironically, he wrote this while sitting in Highwood House, the family home of Bird Society Vice-Presidents Captain and Mrs Suckling, which he describes as “magnificent”, adorned as it was with portraits of generations of Sucklings dating back to Elizabethan times.

In early July The Times reported that a delegation of scientists had visited Mr Hanbury [I assume Robert William Hanbury, then Financial Secretary to the Treasury], with luminaries Lord Lester and Sir Michael Foster bolstering the ranks of the physicists. Hudson’s scorn was searing:

I should have thought that Lord Rayleigh and the other physicists could have beat their own big tom-toms and blown their brass rams’ horns without assistance from others, but it’s a case of let’s all go together and help each other – and let the millions of Londoners go and suffocate in their slums, we don’t care! It always seems to me that the greatest cant of the present time is about the scientist’s love of his kind. But I fear I am boring you about all this.

During the debate, an MP queried that if it has been permissible to put a golf course on part of the landscape here, why not a Physical Laboratory? In response to this Hudson reasoned: “the golfers tho’ they may be fanatics are very harmless when compared with physicists who build laboratories, and their scarlet coats did not create alarm…”

The government abandons the project to build at Kew

The kerfuffle died down for a while, in Hudson’s surviving letters at least, before suddenly the conclusion of the campaign sparked vividly to life again. A scenario is described in Hudson’s letter to Eliza Phillips on 25 November 1900, written after he had been to Kew once again to meet Emma Hubbard:

When I arrived at Kew Gardens station there was Sir William Thiselton Dyer [Kew Director] on the platform, and seeing me alight he cried out “You’ve done the trick!” When I asked what he meant by those strange slangy words (so unbecoming in the mouth of a person in his position) he said that the Government had finally abandoned the project of building at Kew, so that danger to the Gardens and Old Deer Park was over.

Sir William Turner Thiselton-Dyer (pictured in The Gardeners’ Chronicle in 1899), who was Director of Kew Gardens from 1885 to 1905.

This story within the story of Hudson the campaigner helps bring into focus not only the modus operandi of the early SPB and his role within it, but I think also the nub of the force that drove him. Proposals to put any large building on his beloved Kew Gardens would have met with his ire and opposition, but there is something about physicists being behind it, men of science who ought to know better but who, in his view, might know the price of everything and the value of nothing, that made this campaign one especially close to his heart, and soul.

Note: The RSPB today counts Hudson’s Times letter among its collection of pamphlets, this one called Kew Gardens and Old Deer Park in which his letter was reprinted in full.

- You can read more on Conor Mark Jameson’s biography of Hudson at Finding W.H. Hudson – Author Interview – Pelagic Publishing