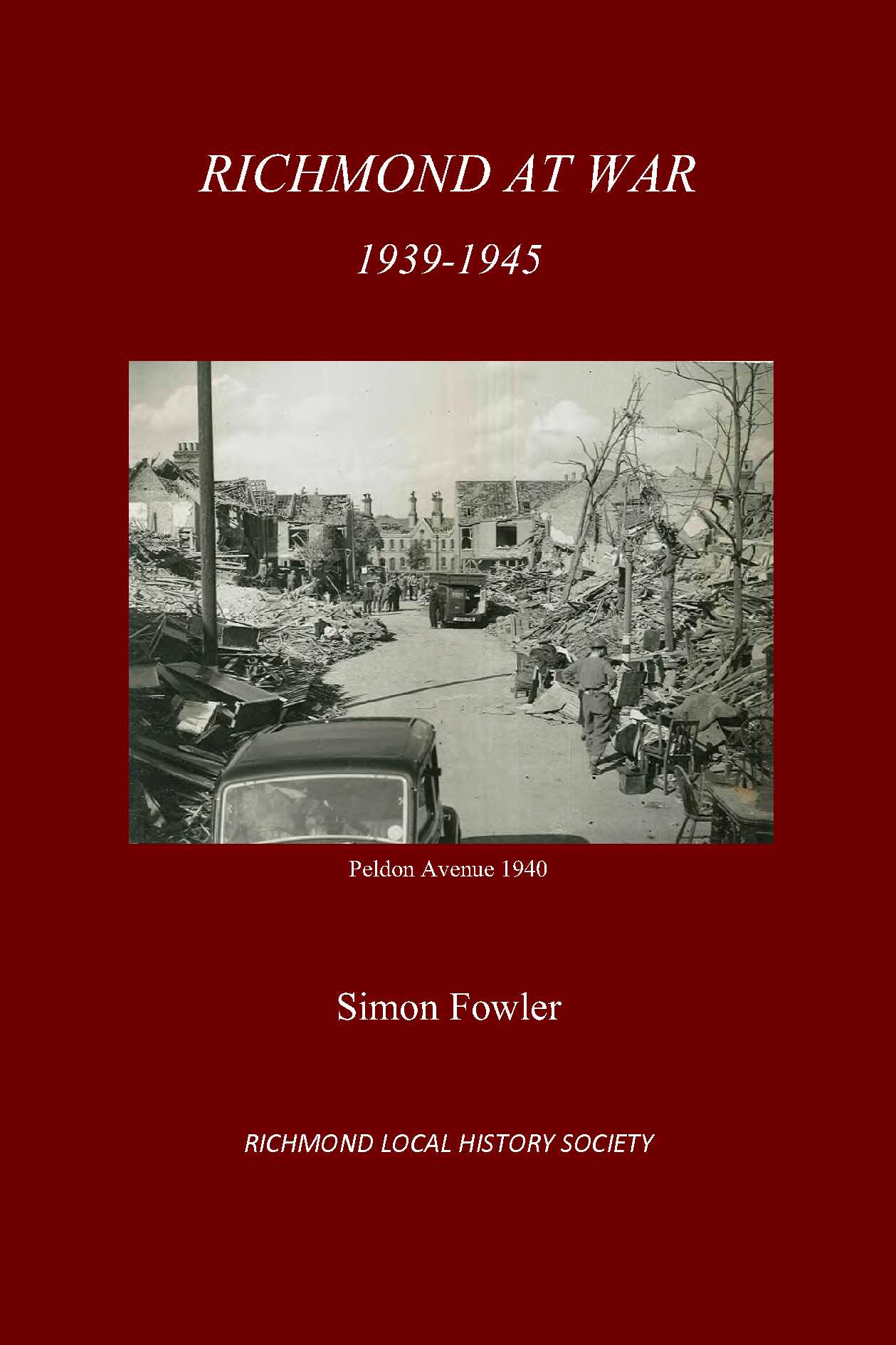

from the Richmond Local History Society’s book Richmond at War 1939-45 by Simon Fowler, published in September 2015

from the Richmond Local History Society’s book Richmond at War 1939-45 by Simon Fowler, published in September 2015

The story of brave Cockneys grinning and bearing it during the Blitz in 1940 is really a myth. The start of German air raids on Docklands and the East End in late August saw many panicky families flee the bombing. Some sheltered in Epping Forest, while others made it as far as Reading and Oxford. Frank Lewey, the Mayor of Stepney, who arranged the despatch of thousands of desperate men, women and children, wrote later that he and his staff were…

far too busy to keep records of the evacuees. It was all we could do to get them out of London fast enough. We did not know where they had all gone, or all who had gone there, except that one hundred and fifty had gone to Ealing, two hundred and thirty to Richmond and so on.

In Richmond hundreds of refugees arrived at short notice on 12 September. The Richmond and Twickenham Times reported that:

A thousand men, women and children arrived, after a four-hour journey down river by barge or in pleasure launches. The first relay arrived at about 12 o’clock; a later party were landing just as an air raid warning sounded and so had to take shelter under the arches by the riverside immediately, and the last 600 arrived so late that they could not be billeted…, but had to spend the night at the cinema sleeping on the chairs or the floor.

They did not receive a warm welcome – in contrast to the myth of Britain pulling together. Richmond’s middle-class home owners were reluctant to take in strangers, http://premier-pharmacy.com/product-category/anti-anxiety/ particularly those from a different social class.

The Mayor, H A Leon, appealed for help:

Inconvenience will inevitably be felt by the householders on whom they were billeted, but this inconvenience is negligible compared with the unhappy circumstances of those who have had to leave their homes. I appeal to all to their utmost to meet this emergency in a happy spirit of co-operation.

Margaret Scudamore played host to a little girl: “who looked with disfavour on the bathing facilities provided and such innocuous foodstuffs as we could muster, and longed only for the joys of her companionable cul-de-sac and piquant pickles.”

Not everybody was so hospitable. Writing after the war, local newspaper the Richmond Herald remembered:

Some householders accepted evacuees reluctantly and did nothing to make these people comfortable, with the result that a large number of East Enders left their billets at night and slept in public shelters and walked the streets by day. Often families had to be billeted in different houses and the fact that they wanted to meet each other during the day led to further trouble. Gradually these were smoothed out… considering the large numbers of persons dealt with there were few cases of dirty conditions.

Most East Enders soon returned home because they were homesick or just worried about what had happened to their houses and possessions.

- Simon Fowler is a professional history researcher, writer and tutor. Richmond at War 1939-1945 is available from the Richmond History Society, price £6.50 (£5 members), and can be ordered online. There will be a dramatised reading from the book at the Duke Street Baptist Church, Richmond at 8pm on 12 October.