With the news that the Royal Star & Garter Home was off on its travels, Richmond History seized the opportunity to celebrate its colourful life on the crest of Richmond Hill. The Star & Garter featured in no fewer than three of the articles in our 2008 journal.

In the 19th century the Star & Garter was the most glamorous hotel in Britain, the haunt of royalty and the literary establishment. John Cloake’s article, ‘That Stupendous Hotel’, described Dickens celebrating the publication of David Copperfield there, with Tennyson and Thackeray among his guests. Thackeray apparently found it a bit overwhelming: ‘where, if you go alone a sneering waiter with his hair curled frightens you off the premises; and where if … you look out of the window you gaze on a view which is so rich that it seems to knock you down with its splendour – a view that has its hair curled like the swaggering waiter.’ This picture by Edward Prentice includes the famous view, along with a group of Dickens’s carousing friends, in this case somewhat dismayed by the size of the bill.

In the 19th century the Star & Garter was the most glamorous hotel in Britain, the haunt of royalty and the literary establishment. John Cloake’s article, ‘That Stupendous Hotel’, described Dickens celebrating the publication of David Copperfield there, with Tennyson and Thackeray among his guests. Thackeray apparently found it a bit overwhelming: ‘where, if you go alone a sneering waiter with his hair curled frightens you off the premises; and where if … you look out of the window you gaze on a view which is so rich that it seems to knock you down with its splendour – a view that has its hair curled like the swaggering waiter.’ This picture by Edward Prentice includes the famous view, along with a group of Dickens’s carousing friends, in this case somewhat dismayed by the size of the bill.

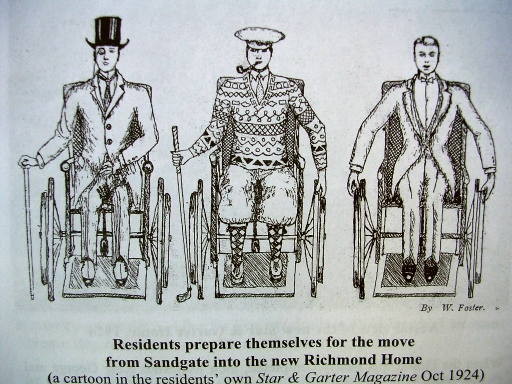

Judith Church’s article, ‘The Royal Star & Garter Home’, described how the hotel then became the home for disabled heroes of World War I. They ran their own magazine. This cartoon, drawn when they were waiting for the home to be rebuilt in the 1920s, typifies their extraordinary courage in the face of a lifetime of dependence. The last veteran of that war died in 1996. The home survived to become a pioneering centre of medical care and treatment for the disabled, generously supported by royalty and by national personalities such as Vera Lynn, Thora Hird, Bamber Gascoigne and Simon Weston.

Judith Church’s article, ‘The Royal Star & Garter Home’, described how the hotel then became the home for disabled heroes of World War I. They ran their own magazine. This cartoon, drawn when they were waiting for the home to be rebuilt in the 1920s, typifies their extraordinary courage in the face of a lifetime of dependence. The last veteran of that war died in 1996. The home survived to become a pioneering centre of medical care and treatment for the disabled, generously supported by royalty and by national personalities such as Vera Lynn, Thora Hird, Bamber Gascoigne and Simon Weston.

VIPs were not always good news. In Steven Woodbridge’s article on ‘Fifth-column fears in Richmond’ we found that in World War Two another VIP, famous in his time and a governor of the Home, was imprisoned for his fascist views. Fascism, then as now, was still a force to be feared.

This picture of hire boats lined up by Kew Bridge is a reminder of the huge leisure trade run by the Williams family at the turn of the nineteenth century. In ‘Kew Riverside 1820-1920’, David Blomfield explored their fortunes along with those of Kew’s other leading boatmen, the Laytons and the Humphreys – all of them colourful examples of those families that clawed their way up into the burgeoning Victorian middle class. The Laytons lived almost next door the royal http://premier-pharmacy.com/product-category/cholesterol-lowering/ family’s holiday homes on Kew Green; the Humphreys were employed as toll keepers by the City in a house that backed on to the huge bargehouse that held the Lord Mayor’s barge; the Williams catered for the crowds that passed their wharf on the way to the Botanic Gardens. In each case apparently the key factor, then as now, was location, location, location.

This picture of hire boats lined up by Kew Bridge is a reminder of the huge leisure trade run by the Williams family at the turn of the nineteenth century. In ‘Kew Riverside 1820-1920’, David Blomfield explored their fortunes along with those of Kew’s other leading boatmen, the Laytons and the Humphreys – all of them colourful examples of those families that clawed their way up into the burgeoning Victorian middle class. The Laytons lived almost next door the royal http://premier-pharmacy.com/product-category/cholesterol-lowering/ family’s holiday homes on Kew Green; the Humphreys were employed as toll keepers by the City in a house that backed on to the huge bargehouse that held the Lord Mayor’s barge; the Williams catered for the crowds that passed their wharf on the way to the Botanic Gardens. In each case apparently the key factor, then as now, was location, location, location.

For public authorities works of art can be embarrassing gifts. Too often they attract graffiti and derision rather than admiration. None more so than Richmond’s notorious ‘Bulbous Betty’. This statue by Alan Howes now presides over the calm waters of a pool at the top of the Terrace Gardens, eliciting little more then polite puzzlement among passing pedestrians – neatly caught in this painting by Ron Berryman. She seems wonderfully oblivious of the extraordinary furore she provoked on her arrival there in 1952.

For public authorities works of art can be embarrassing gifts. Too often they attract graffiti and derision rather than admiration. None more so than Richmond’s notorious ‘Bulbous Betty’. This statue by Alan Howes now presides over the calm waters of a pool at the top of the Terrace Gardens, eliciting little more then polite puzzlement among passing pedestrians – neatly caught in this painting by Ron Berryman. She seems wonderfully oblivious of the extraordinary furore she provoked on her arrival there in 1952.

The setting is appropriate, as her true title is ‘Aphrodite’, echoing perhaps Botticelli’s painting of her birth off the coast of Cyprus. The style, however, is that of the modernist idiom of the 1950s, and it excited outrage among some of the councillors and even more of the citizens of Richmond. Controversy raged in the letters columns of the Richmond and Twickenham Times, ‘Bulbous Betty’ being only one of a number of derisory nicknames suggested in a heated correspondence that the editor brought to a close after no fewer than 84 letters. She was described as being an insult to human form, and schoolchildren were forbidden to look at her. One letter declared the ‘the sculpture is as disturbing to gentlemen, as Father Thames is to maidens’. Ron Berryman’s article, ‘The Disgracing of Aphrodite’, wittily described how she survived what eventually became a matter for national debate.

Other articles in this issue of the journal covered the development of Kew Road, the origins of a Richmond pressure group, pleasant Sunday afternoons at the Congregational Church and the odd case of a toddler lost and found on the towpath in 1902.

The journal is priced at £5 (£4 to members). To find out how to buy a copy go to our Bookshop page.

Find out more about other issues of Richmond History:

A free index to issues 1 to 38 of Richmond History is now available online.