This is the text of a talk given by Nick Selwyn to the Richmond Local History Society in 2009

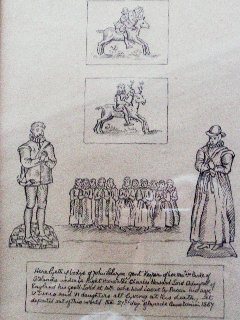

The first member of my family who can with any certainty be said to have lived in the proximity of Richmond is the redoubtable John Selwyn who has been described as: Gent and keeper of her Majesty’s Park at Oatland. A brass plaque to his memory can be found, set in the north wall of St. Mary’s Church, Walton-on-Thames. The brass commemorates the death of John Selwyn in March 1587, that is shortly after the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots at Fotheringay and the year before the Spanish Armada. The Queen of England must have been in a somewhat agitated state around this time which cannot have been lessened by the remarkable feat that her keeper was to perpetrate before her very eyes. A narrative of what took place appears in F. Grose’s Antiquarian Repertory of 1773 in which an aged sexton of the church recounted the story as follows:

“In the reign of Queen Elizabeth, John Selwyn was extremely famous for his skill, strength and agility in horsemanship, specimens of which he exhibited before the Queen at a grand stag hunt at the Park, where attending, as was the duty of his office, he, in the heat of the chase, suddenly leapt from his horse upon the back of the stag, both running at the time at the utmost speed, and not only kept his seat gracefully, in spite of every effort of the affrighted beast, but drawing his sword, guided him towards the Queen, and coming near her presence, plunged it in his throat, so that the animal fell dead at her feet.”

A different version of this exploit, certainly erroneous, suggests, however, that at the very moment Selwyn thrust his sword into the stag, the animal threw back his head apparently in retaliation and pierced its rider’s heart with its antlers. They both fell dead together – arguably a more accomplished feat if it had indeed been intended!

Sadly, no record of the Queen’s reaction is recorded or whether my ancestor was suitably rewarded for his antics, but we do know that she possessed the heart and stomach of a lion, so we must assume that she witnessed this swashbuckling event with her customary Sang-Froid. Many a time in her reign some attention-seeking courtier must have attempted to catch the Queen’s eye with similar feats of derring-do whether they be a Dudley, Raleigh, Devereux or even a Selwyn.

This early record of my family is interesting from three points of view:

- First, it underlines the importance of the Royal Hunt and service to the Crown as dominant themes that overarched the development of Richmond and its surrounding Parks as playgrounds for the monarch and his or her court. It also provides a clue as to the later social and material advancement of the Selwyn family when they came to settle in this area.

- Secondly, these brasses show John Selwyn and his wife Susan in the everyday clothes of the end of the 16th century. If you look closely you will see Selwyn wearing a hunting horn at his side, which would have been the badge of his office.

- Finally, the existence of eleven surviving children in the 16th century, five boys and six girls, is an extraordinarily rare occurrence and heralds a happy fecundity of the Selwyn gene, giving ample promise for the proliferation of future generations.

Let us now turn to the family tree from which it can be clearly seen how this early promise was, as it were, brought to fruition! It never ceases to astonish me how quickly and exponentially families multiply. High infant mortality and untreatable diseases in the 18th and 19th centuries certainly snuffed out a high percentage of infant lives and necessitated a ready supply of heirs and spares. And yet by and large miraculously life prevailed over death! My family was no exception.

The story tonight is about Richmond and about how and why Richmond developed and grew as it did viewed through the perspective of one family. I would now like to introduce you to the first of the main protagonists in my family who lived in and played a role, quite a big role in some cases, in shaping Richmond during the 18th and 19th centuries. They left their mark on our town in a number of distinctive ways, whether in the naming and pattern of our roads and streets, the evolution of local government, or the building of two of our churches.

In this slide we can see the family descent from William Selwyn, who died in Jamaica in 1702, where he had served as Governor-General. He had been a career officer in the King’s Guards under Charles II and James II and had made his peace with William of Orange during the Glorious Revolution. He had fought in the wars against Louis X1V and had risen to the rank of Major General. This is a portrait of him by Sir Godfrey Kneller, the court painter, who coincidentally lived at Kneller Hall in nearby Whitton, in a house he had built in 1709.

At that time the family lived at Matson, a smallish but charming Elizabethan Manor house situated in the Cotswold Hills, a few miles south-west of the city of Gloucester. The house and land was acquired by Jasper Selwyn between 1597 and 1614. He was a barrister and later Treasurer of Lincoln’s Inn, thereby commencing a close link between the Selwyns and Lincoln’s Inn, which was to re-emerge in the 19th century.

The Estate enjoyed a truly arcadian setting in the 18th century, which today has sadly been completely destroyed by the worst kind of urban blight imaginable! Here we find our first Richmond link. There is a Matson Villas to be found at the junction of Sheen and Church roads. William Selwyn married well and was wealthy enough in 1694 to purchase a fine town house in Cleveland Row, St James’s, opposite the Palace. The house standing is the second house on this spot and is today the headquarters of Pilkington Glass. His wife Albinia Betenson inherited property in Chistlehurst, Kent, a fact which later became immortalised in Richmond with the naming of Chistlehurst Road. I will be coming back later to Selwyn related and inspired Richmond and Kew street and road names. The name Albinia was henceforth frequently used as a Selwyn family name.

Matson gained prominence in August 1643 during the Royalist siege of Gloucester when the House was requisitioned by Charles 1 with his two sons Charles and James. At that time there were springs on the steep hill behind the house, which controlled the city’s water supply, so Matson held a strategic advantage for the Royalists. The two boys spent much of their time confined to an attic room where they whiled away their days carving notches in the windowsill. Ultimately the siege was called off on 5th September, when the Royalists learned of the advance of the Earl of Essex. The King’s failed attempt to capture Gloucester was one of the turning-points in the Civil War.

The contrast between this small rural manor house and their normal palatial London surroundings must have been pretty stark and it is recorded that on asking their father when they were returning home, their father replied despondently: “Sadly My boys methinks I have no home to go to.”

Let us now return to the 18th century and the next generation of the Selwyn Lineage – the three sons of General William Selwyn: John, Charles and Henry. The middle son Major Charles was to leave the biggest Selwyn footprint in Richmond. In his definitive book Kew Past, David Blomfield, our esteemed Chairman, described him grandiloquently as the The First Selwyn. Like their father, the three brothers all served in the Army and the eldest brother John rose to the rank of Colonel and acted as ADC to the Duke of Marborough at the battles of Malplaquet and Blenheim. An ADC or the galloper was responsible for carrying messages between different sections of the battlefield. The famous Blenheim tapestries at Blenheim Palace give a good flavour of what a battle scene in the 18th century was like. In the heat of battle, Selwyn’s role was an arduous and extremely dangerous activity with shells, bullets and God knows what flying around everywhere. Amidst all the carnage, Malplaquet was a notoriously bloody conflict, he and presumably his horse managed to survive, however, which lends our family motto Dieu me Garde added credibility.

Brother Charles of whom sadly no portrait survives resigned his commission in 1715 and found a new career joining the Household of the new Prince of Wales, George Augustus of Hanover as Gentleman Usher and later first Equerry to his wife Caroline of Ansbach. Caroline it was who incidentally had Maids of Honour Row built for her ladies-in-waiting on Richmond Green in 1724-26. It was this appointment that brought Charles Selwyn to Richmond in 1718, since George and Caroline had chosen Richmond Lodge –formerly Ormonde, Lodge, in what is today Old Deer Park, as their country residence. In 1718, Charles married at Somerset House, Mary, the widow of William Houblon, a nephew of Sir John Houblon, the first Governor of the Bank of England. The Bank of England was founded in 1694 at a time of similar national peril as we face today as the government desperately sought to raise funds to prosecute the war against the might of Louis X1V. The Houblons were wealthy Huguenots and a prominent Richmond family, who gave their name to Richmond’s oldest surviving Almshouses still in their original state founded by Rebecca Houblon in 1759. Rebecca lived with her sister in Ellerker House, which we know today, of course, as the Old Vicarage School.

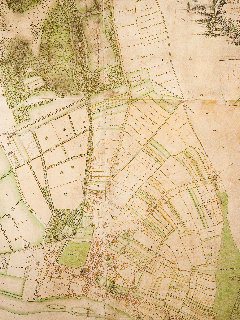

In 1720, Charles and Mary bought a large area of farmland, mostly running up the slopes of the hill and stretching down to Kew parallel with the Kew Road. The land consisted of 105 acres and is well documented on early maps and plans, particularly Thomas Richardson’s map of 1771. The title to much of this land was copyhold, which meant that all transactions had to be registered and approved by the Manor Court. A curious feature of copyhold, under a branch of property law known as Borough English was that all land held by copyhold passed down through the youngest son or daughter, as it indeed did in the case of the Selwyn Estate. You will see reference on this map to a Lower Shot and Lower Dunstable Shot, much of the Selwyn land was contained in these areas. I was intrigued to find out exactly what a Shot represented as a unit of land measurement. We are all of course familiar with Parkshot. My research revealed that a Shot is roughly equivalent to one furlong or 40 poles. Does that help? Probably not! Well a pole is the same as a rod or perch and apparently refers to the length of stick that the ploughman’s son used to control the team of oxen, sometimes up to four pairs. To give us a clearer idea then one furlong would be equal to a furrow length of 220 yards. Eight furlongs would make a mile. You might care to bear this in mind the next time you place your bet at the races or are negotiating the rent on your allotment! I have to concede, however, that John Cloake did not subscribe to this theory when I mentioned it to him, commenting that the boy’s stick would have to have measured over 15 feet in length!

As we have just seen the land around Richmond was parcelled up into small fields, which Charles Selwyn and other owners were able to let off to local tenant farmers for raising crops. With his income secure, Charles was now able to turn his attention first to national issues in Parliament and later to the provision of welfare in local government here in Richmond. The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 brought the War of the Spanish Succession to an end and amongst other territorial gains England, of course, acquired its beloved Gibraltar. The end of the war unleashed a wave of philanthropic zeal over England; this was the age of Thomas Guy, the smart guy who sold out at the height of the South Sea Bubble and used the proceeds to build Guy’s hospital; General Oglethorpe the founder of Georgia, the last English colony founded in America, named after George II, mainly for poor debtors; Thomas Coram and his foundling hospital in London. There was a growing concern in government, both at national and local level for the plight of the poor and disadvantaged in society and the Selwyns were not immune to the influence of this Zeitgeist.

After a spell as MP for Ludgershall in Wiltshire, which was a classic example of a rotten borough being owned by his brother John who could therefore nominate any candidate he wished, Charles turned his attention to local affairs in Richmond. In 1725 he had become a Justice of the Peace in the Surrey Quarter Sessions and a member of the Richmond Vestry- offices which he held until his death in 1749. The scandalous state of London’s prisons became a big issue about this time and Charles worked hard to improve the condition of the hapless and in many cases innocent inmates. He helped to bring about improvements first to the Surrey House of Correction and then the notorious Marshalsea. Those who watched the BBC’s recent poorly scheduled adaptation of Little Dorrit will be familiar with the terrible conditions prevalent in such prisons in the 19th century, so you can imagine what they must have been like a hundred years earlier! Two reforms carried out by Charles and the other Surrey Magistrates saw to it that in future gaolers should be paid out of public rates instead of allowing them to extract a living from their prisoners. And secondly, that prisoners received a modest provision of bread again to be paid out of rates, instead of them having to rely on charity or their relatives for their food.

Although Charles was co-opted onto the Richmond Vestry in 1726, he preferred to direct his energies through another body, the parish meeting, a more vigorous and broadly based organ of local government. He made his mark at the first Parish meeting he attended by getting his declaration passed that the inhabitants of Richmond “as subjects of the Crown of Great Britain have a natural right to look into the accounts of the disposal of all such moneys as are levied upon them”. A declaration we might well bear in mind today after our local Council in their wisdom has just hiked our Council Tax at a hefty rate way above inflation. At the following meeting, it was revealed that monies levied in 1721 for new fire-engines had not been used and this oversight that was speedily rectified. An important issue was the discussion and implementation of the New Poor Law Act of 1722, which came to be called the Workhouse Test Act for its main purpose was for every Parish to provide a workhouse. It was agreed that if a family or person could not cope on account of age, disability, illness or unemployment they could be given shelter, food, clothing etc from the rates, but only if they were prepared to enter the workhouse. In 1729, the parish meeting found temporary accommodation for a workhouse in a group of cottages probably behind where the Orange Tree Tavern is today. The following year they took over a lease of a large 17th century house called Rump Hall in the Petersham Road and in 1787 a new site was found in the area of Pesthouse Common, the area of land to the west of Queen’s road adjoining the park and the cemetery. The main building was paid for by George III who on visiting the building, which included a lunatic asylum, was apparently not unduly perturbed when the Master demonstrated the use of the newly invented straitjacket, an instrument with which our unfortunate monarch would have been more than familiar during his time at Kew Palace!

Charles died on 9 June 1749 at his house at West Sheen and is buried in the chancel of St Mary’s Church, Hampton, but his successors continued his pioneering work. His achievements were praised by the Webbs in their magisterial work on English local government in which they described how “between 1717 and 1730 Charles Selwyn organised the government of Richmond “as one of the leaders of the Parish”. Richmond continued to set the pace in welfare administration in England as is proved by the achievement of William Thompson in making Richmond the first local authority in the country to provide good housing for the less well-off in the Manor Grove Estate in 1892.Charles made one final important legacy to Richmond – a line of heirs who not only inherited his property in Richmond, but also continued his family’s tradition of hard work in the public service. In his will, having no children of his own and abiding by the dictates of copyhold law, he passed over the children of his elder brother John, including his enigmatic younger son George Augustus, who you will hear more about anon, seeing more potential in the future of his other nephews; the two sons of his younger brother Henry, who died in 1734, leaving six daughters and two sons by his wife Ruth Compton.

Charles decided to bequeath the 105 acres valued at £192 a year to his brother’s younger son William, who came to live in Richmond in 1761, first at Larkfield Lodge, just off the Lower Richmond Road, and then a house called Pagoda House, later named Selwyn Court, built for him in 1810 on the Kew Road on the site of the present Christ Church in the area of Selwyn Avenue.

As we now begin to enter the second half of the 18th century, we have to consider the next generation of Selwyns, particularly the notorious George Augustus Selwyn, whose name crops up so frequently in the literature and letters of this period.

His father, Colonel John, whose elder son John sadly predeceased him in 1751, left a life interest in the Matson Estate and his elegant London house to his second son George. George was by the standards of the time a very http://premier-pharmacy.com/product-category/anti-fungal/ wealthy man, and having acquired several juicy sinecures was able to live a comfortable gentlemanly life of sophisticated indolence, frequenting the Clubs of St James’s, he was incidentally a founder member of Whites and alternating his time between London, Richmond, the family estate in Gloucestershire and his beloved Paris. High society in London was made up of a relatively small group of people, all of whom were more -or- less acquainted with each other. It was indeed a small world and the latest jokes and bon mots of the wags and wits of St James’s quickly spread around the country. George was the foremost wit of his day, although his jokes tend to fall rather flat today as we can only imagine their contemporary context and the languid manner in which they were delivered. I present two of his more accessible jokes for your judgement: on learning that a well- known debt-ridden Mr Foley was crossing the Channel to the Continent in order to escape his creditors, Selwyn opined drowsily from his leather arm-chair in Whites, that “this was a pass-over that would not be relished by the Jews”. When a man called Fox had been hanged and Charles James Fox asked him if had been to the execution, George replied “No, Charles I never make a point of attending a dress rehearsal.”

In his entertaining, though perhaps rather dated book , The Age of Scandal, T. H. White devoted a chapter to Selwyn headed the Necrophilist and it is true to say that George did indulge a macabre interest in death, torture and execution. He enjoyed his frequent visits to the Tyburn Gallows near the spot where Marble Arch is today and according to Horace Walpole witnessed the executions at Tower Hill of the great highland Jacobite Earls after Bonnie Prince Charlie’s failed invasion of England in 1745. Lord Holland on his deathbed told the servant “The next time Selwyn calls, show him up: if I am alive I will be pleased to see him, and if I am dead he will be pleased to see me!” George often attended the infamous Hell-Fire club at Medmenham Abbey near Henley- on-Thames, where the more depraved members of society indulged in satanic rituals and witchcraft.

The full story of George Selwyn really merits a separate treatment of its own, so I will conclude with a reference to his close and life-long friendships with two important Richmond residents, namely William Douglas, Earl of March, the 4th Duke of Queensberry one of the richest and most debauched men in England and Horace Walpole. The Duke owned an imposing mansion overlooking the Thames, on the spot where the Queensberry mansions block of flats is today along Friars Lane, just off the Green. He enjoyed the nickname Old Q as this letter was prominently displayed on the doors of his carriage.

Queensberry House was used by the Duke for entertaining the leading members of English society and Mr William Wilberforce vividly recounts the story of one such Soiree. “I remember dining when I was a young man with the Duke of Queensberry at his Richmond Villa. The party was very small and select- Pitt, Lord and Lady Chatham, the Marchioness of Gordon and George Selwyn were among the guests. The dinner was sumptuous, the views from the villa quite enchanting and the Thames in all its Glory:” but the Duke looked on with indifference –“What is there”, he said, “to make so much of it in the Thames? There it goes flow, flow, flow always the same.” Fortunately for us it still continues to flow today to our greater enjoyment and appreciation. The Duke enjoyed many affairs during his long life and justifiably earned the sobriquet the Rake of Piccadilly. In his dotage he was reputed to take a daily bath of milk, a matter of considerable concern to the local residents who feared that the used milk in which the duke’s whizzened and gnarled body had immersed and abluted may have been recycled into their own supply. One product of his many amorous and normally carefully conducted liaisons, the daughter of a particularly dissolute Italian Marchioness Fagnani, was Maria Emily, otherwise known as Mie Mie, later adopted by his close friend George, who cherished and raised the child as if she were his own daughter. Mie Mie was eventually to inherit the bulk of the Selwyn Estate to the extent of £30,000 and also received a massive bequest from the Duke making her an extremely rich young woman. Unfortunately like her mother she was attracted by the more disreputable men in London Society and proceeded to marry the dissolute third Marquess of Hertford who together with his putative son William Wallace amassed a priceless art collection, which today can be viewed at the Wallace Collection. Several Selwyn items, which Mie Mie acquired as her inheritance of Matson House are on display at the Museum, including a fine bust of Charles I, which her guardian George commissioned from Francois Roubiliac in 1759, presumably to celebrate the King’s visit to Matson back in 1643.The bust may have been based on Van Dyke’s triple portrait of the Martyr and from a cast of Bernini’s famous bust, which perished in the Whitehall palace fire of 1698.

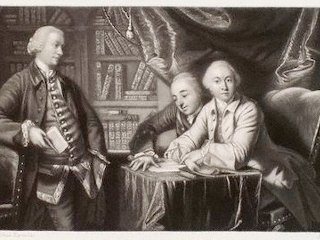

Horace Walpole, the son of England’s first Prime Minister, Sir Robert, was one of Richmond’s most illustrious residents, whose Gothic Villa in Strawberry Hill, today a catholic teacher training college, was also a favourite meeting place for men of Letters, particularly the so-called Out of Town Set. In 1754 Horace wrote from Strawberry Hill to Richard Bentley: “ I am here quite alone; Mr Chute is setting out for his Vine; but in a day or two I expect Mr Williams, George Selwyn and Dick Edgecombe. You will allow that I do not admit anybody within my cloister, I choose them well.” This group of friends had formed a custom of coming down to stay at Strawberry Hill at Easter and Christmas time, gatherings which Walpole came to describe as “my out-of -town”. A conversation piece of the Out of Town group was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1759.The scene is set in Walpole’s library. Walpole who commissioned the work was highly delighted with the result and later wrote, after Edgecombe’s untimely death in 1761: “Did you see the charming picture Reynolds painted for me of him, Selwyn, and Gilly Williams? It is by far the best thing he has executed.”

I am finally going to make mention of three further members of my family who had a very close association with Richmond and its environs and it will be helpful at this juncture to return again to the Family Tree.

I have already made reference to William Selwyn, who inherited the Richmond Estate from his uncle Charles. William was an astute lawyer, who continuing the family tradition, became Treasurer of Lincoln’s Inn, whilst residing at Selwyn Court. He in turn was succeeded by his son, also William, who likewise proved to be an able lawyer and had the honour of instructing Prince Albert in the niceties of British constitutional law. William was described by the Prince in a letter to Stockmar as “old, bald-headed, lame, with staring eyes, skin like parchment and a voice like a lion”. One wonders whether with all their legal work they had as much time to devote to local affairs as Major Charles, but with their large Estate still intact they would have held a very prominent position in Richmond society and received an enviable income from their land. Whilst stopping at the traffic lights at the bottom of the Lower Mortlake Road as one enters onto the Richmond Circus, if one looks sharp right one can see two intertwined Initials WS dated 1853. This is the monogram of William Selwyn the younger and is one of the few remaining relics of the Selwyn Estate.

The marble memorials of the two Williams together with those of their wives can be seen on the south wall of our parish church. The second William left the Estate to his heir and youngest surviving son, Sir Charles Jasper Selwyn ,Lord Justice of Appeal.

Charles Jasper was a prominent member of Richmond in the mid 19th century and in spite of his pressing legal commitments in London, he was very much concerned with local affairs. The increasing population in an age of church-going was putting great pressure on the parish Church, despite its enlargement with the adding of new aisles and galleries. In the late 1820s it was decided to build a new church, which was founded on land donated by the Selwyn family. Lewis Vulliamy was engaged as the architect to build St John the Divine on the Kew Road. This met the demand for a few years only and soon another church was required for the population on the hill. At the end of Friar Stile road on land given by Charles Jasper, the church of St Matthias, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in Gothic style, soon began to emerge from the ground and after its opening in 1858 became the Richmond landmark that it remains today. As John Cloake writes, the prosperity of Richmond was reflected in the very large provision of almshouses – The Vineyard boasts three! Charles’ name appears as a trustee on plaques outside St Michel’s Almshouses in the Vineyard and also Hickey’s Almshouses along Sheen Road. Charles died at a comparatively young age of 56 at his home in Selwyn Court. Thereafter the house was used less and less by the family, Charles’ children went to live with their uncle George in Lichfield and after a bad fire Selwyn Court was eventually torn down in 1895; the only trace of the house and estate remains to posterity in the name Selwyn Avenue. One other fact of interest connected with Charles Jasper is that on the death of his first wife he married in 1869, the year he died, the widow of Revd Harry Depuis, who had been vicar of Richmond after a career as a school master at Eton College for many years. It seems highly likely that the naming of Eton Street may have some connection here.

The Arcadian bliss of 18th century Richmond, indeed England in general, was rapidly yielding to the demands of a more materialistic and grasping age. The coming of the railways brought about changes that earlier Richmond residents could scarcely have imagined, let alone predicted. The Richmond railway opened in July 1846 and by 1847 it was handling 25,000 passengers a month! As I mentioned earlier the Selwyn fields were mostly let to tenant farmers who made fair profits from supplying London with cereal crops; the advent of the railway dramatically changed the viability of this business as food was increasingly imported from further afield at reduced costs. They switched to market gardening and then fruit farming, but to no avail. Their profits fell and they were no longer able to afford the rent on their land. The owners began to be tempted with offers from developers who were keen to meet and profit from the new demand for houses from the now increasingly mobile and affluent middle class, who wanted to move out of central London.

If we look at the ordnance survey map of Richmond of 1894-6, we will see that although a lot of building had taken place by this time, there were still fairly large tracts of open fields still undeveloped.

As the family property was gradually sold off, it became necessary to build new roads and streets to provide access for the new residents and tradesmen and it was through the names of these new thoroughfares that we have an enduring link with the Selwyn Estate. Two factors made the regular naming of roads essential; first the advent of the Penny Postage from the 1840’s. How else would the Postman know where to deliver his letters? Secondly, the lack of proper and reliable addresses had caused havoc with the 1841 Census. Although originally, the Vestry and today the Council, has the last word in the approval of street names, they have no legal right to the choice of names. By far the largest proportion of new buildings were put up by private enterprise on land privately owned and in Richmond itself some 60 out of 300 or so streets were created on land which at one time belonged to the Selwyn Family. Names were chosen in a random, arbitrary, even at times whimsical way. They could honour a member of the family, a friend or a member of the Royal Family. They could recall their family’s other properties or boast of an ancestor or a propitious marriage from the past. There are so many Selwyn-inspired names that I can only mention a handful here. Lichfield Avenue was named after Charles Jasper’s elder brother George Augustus, who became Bishop of Lichfield after having served 27 years in New Zealand as the first and only Bishop of New Zealand. Dynevor Road, built on Selwyn land in the late 1870s, may have been named after Baron Dynevor, a friend of the Selwyn family and possibly refers to the auspicious marriage in 1794 of Frances , granddaughter of Albinia Selwyn to George Talbot,2nd Baron Dynevor. This same Albinia had married in 1730 Thomas Townshend – hence Townshend Road – and their son, the 1st Lord Sydney, was the inspiration not only of Sydney road, but as Home Secretary also gave his name to the City of Sydney in Australia in 1791

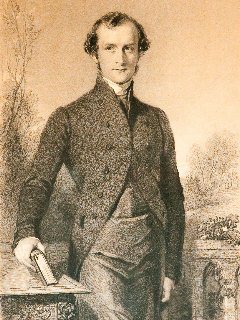

And so we come to the last Selwyn we will meet tonight. George Augustus was the elder brother of Sir Charles Jasper and although he spent the major part of his life, 27 years in fact, overseas in New Zealand, he would have visited the family home in Richmond many times.

It could be argued that George was the most illustrious of all the members of my family, earning a truly international fame. Many books have been written about him, which all testify to his remarkable humanity and that deep sense of duty and public service, which so exemplified our Victorian ancestors. In recognition of his remarkable life, a committee of leading dignitaries decided, after his death in 1878, that a fitting tribute to his memory would be a Cambridge college to be named after him. George was born on 5 April 1809 and we have therefore been able to celebrate his bicentenary in Cambridge only last weekend. 1809 was, incidentally, also the year of the birth of the Rt Hon William Gladstone, who had been a contemporary at Eton and remained a life-long friend. Gladstone wrote the following words after Selwyn’s death in 1878: “I have known him from boyhood upwards, and I will only now say that there is one epithet which I hope will always be associated with his name beyond any other in the recollection of those who loved him and that is the epithet of Noble. George has often been described as a muscular Christian and it is a fact that his athletic frame also enveloped a first-class mind. Like his brothers he would have grown up and relaxed beside the Thames, either at Eton or Richmond and they were both accomplished oarsmen. George incidentally rowed for Cambridge as 7 in the first Oxford and Cambridge boat-race held at Henley in 1829, a close contest which was won by the dark Blues. His early acquaintance with water and rivers was to provide an invaluable aptitude in later years as he negotiated the rivers of New Zealand and navigated thousands of miles through the treacherous seas of the South Pacific as he administered to his flock in those far-flung Islands of Melanesia.

And so our journey tonight draws to its close. We have seen how just one family amongst a myriad of families across our Island danced to the music of their times. John Selwyn, the characteristically opportunistic courtier of Elizabethan England, the gallant soldiers of the Marlborough Wars with their later eyes on preferment at court and rich heiresses, the legal bigwigs of Victorian England, who carefully husbanded the Richmond Estate and finally the muscular Christian, with his staunch and unflinching adherence to those very Christian values that Englishmen and women of his time believed had made their country the most powerful and civilized on Earth.

Had our beloved Richmond changed much over those two centuries? If so had it been for the better or for the worse? This was a question recently posed by our last speaker, Chris May, a few weeks ago at the end of his excellent talk. Such judgements are, of course, highly subjective, but I was moved recently when reading a booklet written by Laetitia Selwyn about her four successful brothers, which provided an unique insight into the sentiments of a Richmond resident in the mid 19th century, in which she wrote: “There is no doubt that the railway, and the consequent increase in population have greatly destroyed the celebrated beauty of the place. In 1817, when my father took possession of the House-that is Selwyn Court- Richmond was quite an aristocratic place of residence. The road to the Hill was through fields and gardens and shadowed by fine trees. Opposite the house lived the Earl of Shaftesbury; by the river stood the mansion once occupied by the Duke of Queensberry; the houses of Mr Osbaldeston, Miss Fanshaw, Lady Anne Bingham etc , and on the hill the Dowager Countess of Mansfield , Lady Morshead and Sir Lionel Darell had their residences. All has now changed. The Marquis of Lansdowne’s beautiful seat converted into a brewery; Lord Pembroke’s house on the Green destroyed and on its site Villas erected; hence the distaste evinced by the youthful members of the family for a place that has become a suburb of London. But there is still the river, the matchless view from the Hill, the beautiful and extensive Park and, last not least, the now perfectly appointed Kew Gardens. It may be mentioned that a large part of the gardens formerly belonged to the Selwyn Estate, but was exchanged by our father for land belonging to the Crown near the Hill. The transfer was recognised in a courteous letter written by order of Queen Charlotte in 1817, and accompanying the gift of a private key to my mother, of which constant use was made , for entrance into the Gardens, when closed to the Public.”