Date/Time

Date(s) - Monday 14 December 2020

8:00 pm - 9:45 pm

Location

Duke Street Church

Categories No Categories

This talk, held at Duke Street Church and also streamed via Zoom, was given by Sylvia Levi, an enthusiastic food historian with a particular interest in what our ancestors baked. She was accompanied by Simon Fowler, a long-standing member of the Society who has spent many years researching Richmond’s history.

John Foley reports on Sylvia and Simon’s talk

The good news: despite the pandemic raging, we were able to meet in person at our usual venue, the auditorium at Duke Street Church. The bad news: the society’s customary Christmas party afterwards could not take place and mounting Covid-19 infections and deaths nationally were already making it clear that further social restrictions were imminent, putting hoped-for Christmas family gatherings at risk.

So, Chairman Robert Smith announced “well, if we can’t taste food tonight at least we can talk about it!” And talk about it was what Sylvia Levi and Simon Fowler did most entertainingly.

Sylvia explained that the traditional date marking Jesus Christ’s birth has been observed over many centuries, with slight variations between nations and religions. But only in early Victorian days did the celebrations assume their modern form. Queen Victoria’s consort Prince Albert imported German traditions, especially lighted Christmas trees, while his contemporary, the celebrated novelist Charles Dickens, wrote in A Christmas Carol and The Pickwick Papers about Christmas being celebrated as a family occasion for eating, drinking, conviviality and festive goodwill. The growth of prosperous Victorian Britain and – especially – a national passenger railway network, allowed families to travel long distances to be together.

If Christmas had never been fixed for late December, you feel it would have had to be invented! Certainly, in the northern hemisphere, which of course is the time of the winter solstice and darkness, coldness and barrenness. The chance for everyone to have a booze-up, a pagan tradition, praying for daylight to return and the growth of new crops. Concurrently with Christian religious observation there was much feasting. Although, Simon said, people did not generally make as much of Christmas as we do today. But what people ate depended upon their social station and their location. In mediaeval times boars were hunted and killed for the Christmas table but, by the 16th century, they were extinct. Yet roast beef was already a popular staple, as well as mutton, goose, peacock, swan and crane. For those with a sweet tooth, sugar was still rare, but there was honey and dried fruit (currants, prunes and dates). It was then customary to place all the dishes on the table at once.

The Tudor period saw the first arrival of turkey from the New World. A century later, the Puritans tried to ban Christmas celebrations, as being satanical practices. The diarist Samuel Pepys describes in 1662 roast pullet, mince pies and plum porridge served as a starter. Over a century later, Jane Austen describes Christmas as a time of dinners and parties, and in the 18th century the sweet course became separately served. The turkey invasion gathered pace in the 19th century to replace goose, with Brussel sprouts from the Low Countries and, in our own time, additions such as parsnips and carrots, eaten to the accompaniment since the 1950s of television!

Christmas Day being a legal “quarter day” when rent and tithes were payable and collected, many landlords would treat their tenants to free food; from bread and cheese, to roast beef dinners. And those in poverty? The workhouse guardians paid for roast beef and plum pudding, though some of the inmates might have struggled to digest the unusual rich fare. Many were the arguments about serving alcohol (beer, punch and nappy ale).

And finally, Simon told the story of little Minnie Cowley of Raleigh Road, Richmond, whose plasterer father was a drunkard and in 1912 spent the family’s Christmas money in the pub. Her poor mother scraped together a few more pence and bought and cooked fish heads to eat on Christmas Day. A burglar stole the plate of fish, to the despair of Minnie’s family. Fortunately, a kind neighbour invited the family to share dinner, so Minnie didn’t go hungry that Christmas.

Much more detail was given by Sylvia and Simon on the composition of fruit punch, nappy ale (very strong!). mulled ale and the transformation of mince pies from savoury to sweet. So whether you cook with the help of Delia Smith, Marco Pierre White or one of the dozens of today’s celebrity chefs, in this extraordinary time of pandemic and restricted social ”bubbles” one hopes you found comfort and conviviality. Happy New Year!

__________________________________________________________________________________________________Unfortunately, current circumstances did not allow us to organise a Christmas party for members, but you might like to make this eighteenth century recipe for mince pies. Our speakers say that it is delicious!

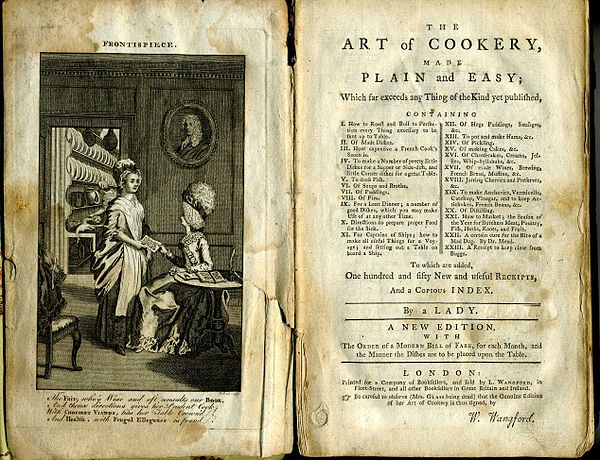

This recipe is from Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery (first published in 1747).

To make mince-pies the best way.

Take three pounds of suet shred very fine, and chopped as small as possible; two pounds of raisins stoned, and chopped as fine as possible; two pounds of currants nicely picked, washed, rubbed, and dried at the fire; half a hundred of fine pipins, pared, cored and chopped small; half a pound of sugar pounded fine; a quarter an ounce, of mace, a quarter of an ounce of cloves, two large nutmegs, all beat fine; put all together into a great pan, and mix it well together with half a pint of brandy, and half a pint of sack [wine]; put it down close in a stone pot, and it will keep good for four months ….

She then goes on to give instructions for actually making the pies

Originally, minc’t or shred pies included meat, sometimes mutton, sometimes beef, but during the eighteenth-century cooks began to leave the meat out. Mince pies were eaten year-round not just for Christmas though and Hannah Glasse also had a recipe for ‘Lenten mincemeat’ which used chopped hard-boiled eggs instead of fat (but also quite a lot of alcohol!)

Here is the recipe suitably modernised with the amounts reduced to more manageable proportions.

Ingredients:

- 300g suet (fresh or from a packet) – you can use vegetable suet, although the taste will be slightly different

- 250g raisins (chopped small)

- 250g currants

- 10 small apples (an older English variety if possible) peeled, cored and chopped small

- 150g brown sugar

- 1/4 tsp ground mace

- 1/4 tsp ground cloves

- 1 tsp grated nutmeg

- 150ml brandy

- 150ml white wine (or dry sherry)

Method:

If you are using fresh suet it must be chopped very finely or grated. Add the wine and brandy, suet and dried fruit to a large non-metallic mixing bowl Then start adding the peeled cored and chopped apples. Do the apples in small batches and immediately put them into the bowl with the brandy and wine (coating them) to stop them going brown. Mix everything in, stirring thoroughly, and cover with a clean cloth or cling film and leave overnight in the fridge. The next day stir the mixture again and then spoon into sterilized jars and seal. Store in a dark, cool place for up to 2 months. The mincemeat will darken as it ages.