Date/Time

Date(s) - Monday 12 March 2018

8:00 pm - 9:00 pm

Location

Duke Street Church

Categories No Categories

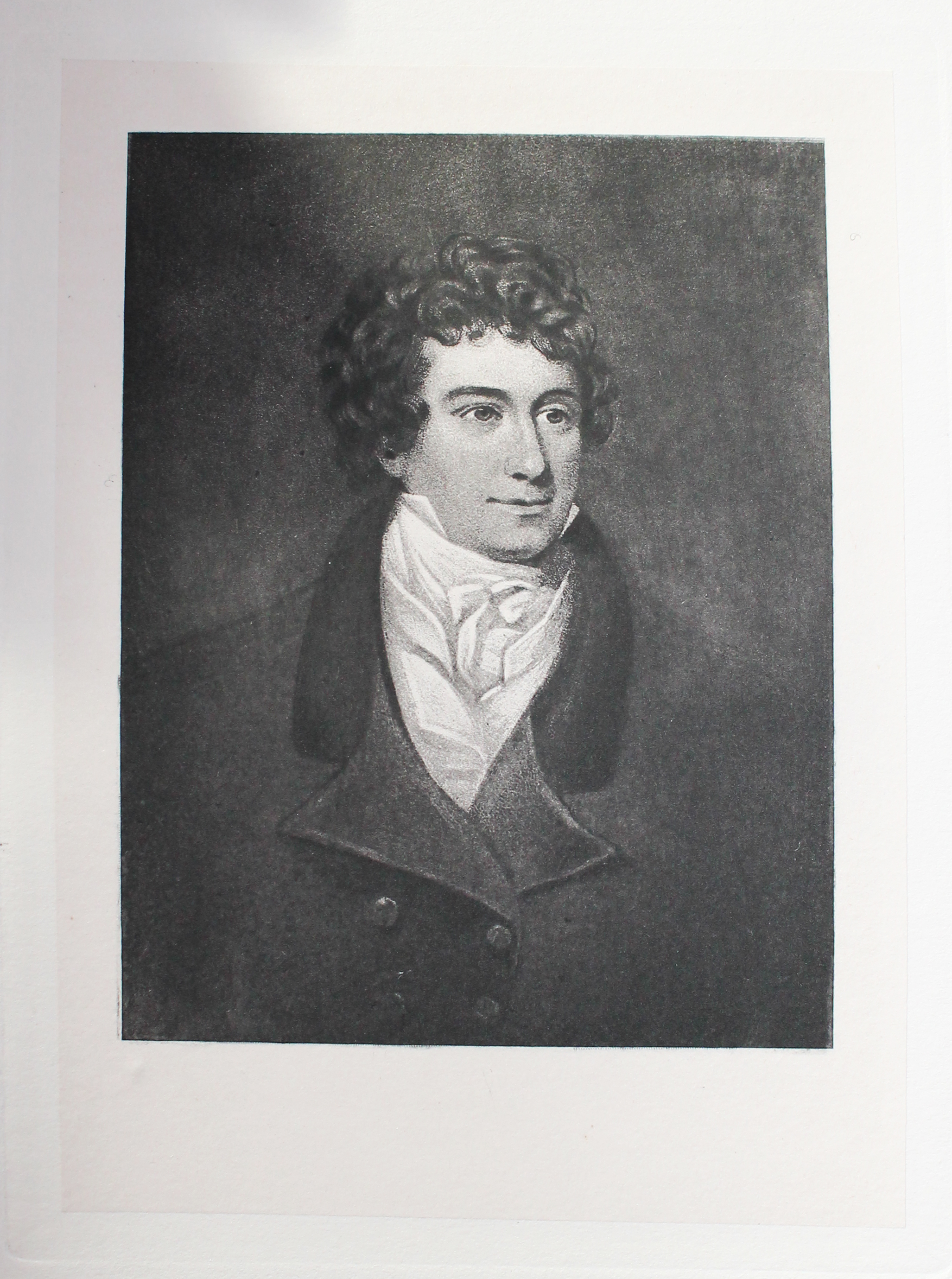

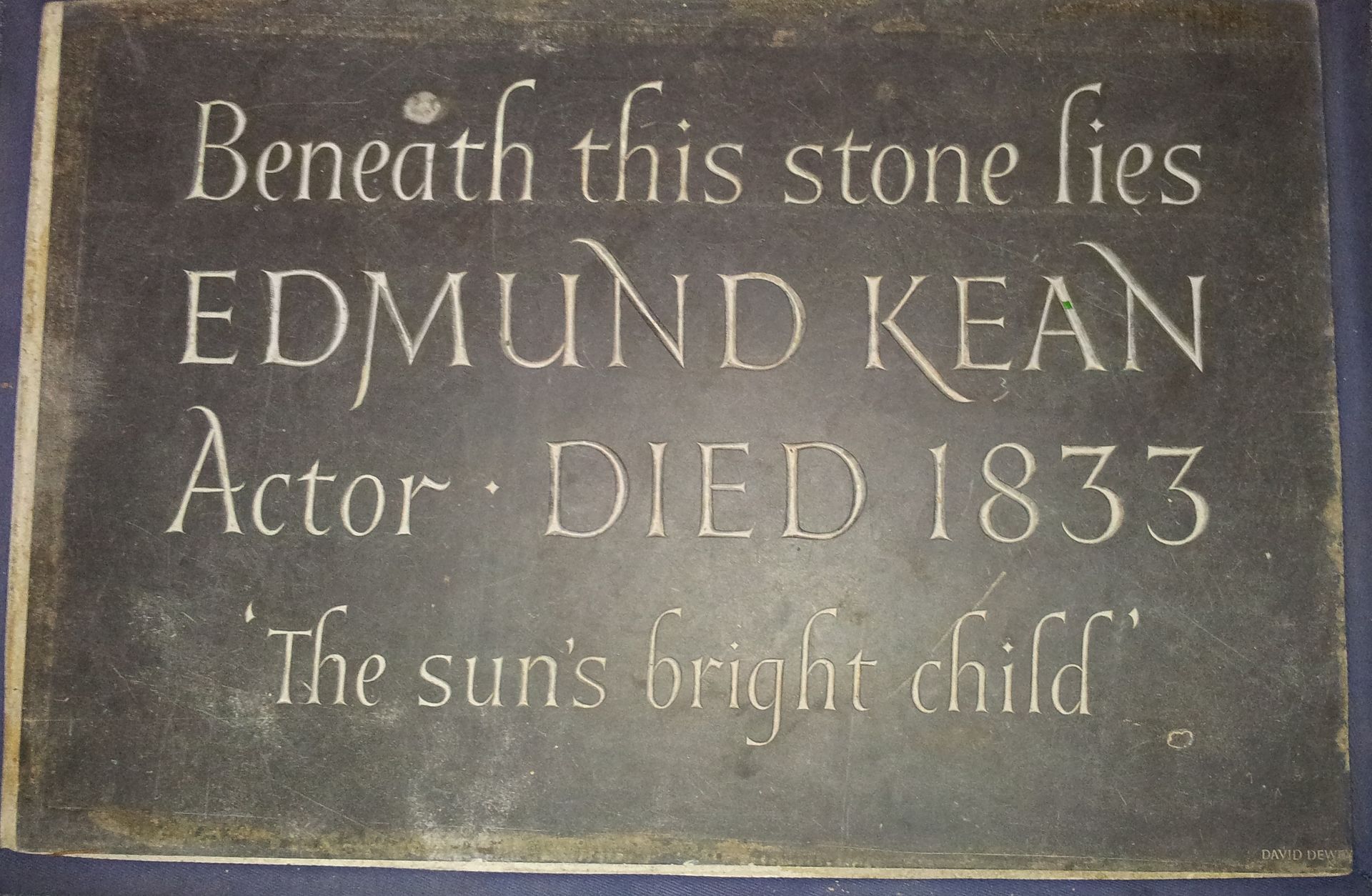

The celebrated British Shakespearean actor, Edmund Kean, died in 1833 in Richmond where, in the last years of his life, he had managed the local theatre. At St Mary Magdalene there is a floor plaque marking his grave and also a wall plaque.

Professor Michael Gaunt FRSAMD, former Chair of The Society for Theatre Research, talked about Edmund Kean, considered by many to be the greatest actor of the nineteenth century.

Kean began as a country actor and in his early years lived through periods of severe deprivation. Success came in 1814 at London’s Theatre Royal Drury Lane when he acted Shylock in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice.

Following this, despite many challengers, he became unrivalled as a tragedian and his great success twice took him to America. Eventually scandal intruded into his life, seriously damaging his career, while at the same time his health deteriorated as a result of hard living. In the closing years of his life he was manager of the old Richmond Theatre and lived in the adjacent house, where in 1833 he died aged 46.

Michael Gaunt began his professional life as an actor. Mid-career, in 1983, he was invited to become principal of the Guildford School of Acting, where he remained for 12 years. He was then principal of the Birmingham School of Speech & Drama until 2002. His special interest is in the English and American actors who starred on both sides of the Atlantic in the first half of the nineteenth century. He was formerly Chair of The Society for Theatre Research and convened the conference Theatre in the Regency Era: Plays, Performance, Practice 1795-1843, held at Cambridge in July 2016.

Paul Bunnage reports on Michael Gaunt’s talk

Professor Michael Gaunt has been an actor, director, acting teacher and a theatre historian. Having devoted many years to wide-ranging research on the English stage and its actors in the first half of the 19th century, he was able to give a very thorough and absorbing talk on Edmund Kean, whose last two years of life were spent in Richmond as manager of the King’s Theatre.

Following in the line of David Garrick, Mrs Siddons and George Frederick Cooke, Kean, along with Cookeand Macready, changed the face of acting in England. He was born in 1787 or 1789 and spent his early years in poverty; largely looked after by his aunt Miss Tidswell (“Aunt Tid”) who had acted at Drury Lane for 40 years, Kean played small parts at the theatre and found, through Aunt Tid and his Uncle Moses, his introduction to Shakespeare, learning many speeches by heart. At the age of eight his talent for mimicry, histrionics, and memorising of speeches was put to mercenary use by his mother, returned to the scene for that purpose.

In 1804, Kean joined a troupe of strolling players based at Sheerness. In 1808 he married Mary Chambers and soon, with two children in tow, began a number of years on the road, performing at Cheltenham, Birmingham and Swansea, acting, singing, even tightrope walking featuring in his performances – a life of hardship compounded by drinking and debt. In 1812 Kean had joined a company which moved to Guernsey but drunkenness thwarted a long-term commitment. Throughout his career Kean was his own man, “neither to be led nor driven” as Aunt Tid had said of him as a young boy.

Kean’s big breakthrough came in 1814 while he was acting at the Teignmouth Theatre. He was spotted in performance by a former headmaster of Harrow School who, much impressed, gave Kean’s name to Drury Lane, which led to a three-year engagement. Kean’s performance as Shylock was a huge success, even saving the Drury Lane Theatre. Hazlitt wrote, “For voice, eye, action and expression no actor has come out for many years at all equal to him”. The actor suddenly found himself earning £4,000 a year and before long £10,000, leading to a life of much generosity, lavishness and profligacy. Kean’s performances electrified audiences – indeed, his playing of Sir Giles Overreach in A New Way to Pay Old Debts led to several faintings and hysterics in the audience and on stage; Lord Byron collapsed in a convulsive fit.

Kean first acted at Richmond in 1817 and again in 1820 when he performed in the role of King Lear. He was famed above all for his Shylock, Richard III, Macbeth, and Othello, probably his greatest role – Hazlitt wrote of the profound pathos and electrifying effect of his acting. The leading actors of this period were always centre-stage and star-billed – and there were no rehearsals! The 1820s was a rich period for his work both here and in America, though seriously marred in 1825 by the scandal of his adultery with Mrs Charlotte Cox.

By 1831, however, he was becoming infirm, his memory was failing and acting became more difficult for him. He had aspired to manage the Drury Lane Theatre but in that year he became manager at the King’s Theatre on Richmond Green (diagonally opposite the present theatre) and moved into the adjoining manager’s house. A young would-be actress, Helen Faucit, contrived one day to meet Kean as he crossed the Green with Aunt Tid: in spite of his slightness, pallor and infirmity she was utterly captivated by his extraordinary eyes and voice. There were a few further performances – as Othello opposite (finally) Macready’s Iago in 1832 and his last ever appearance, in 1833, as Othello with his son Charles as Iago. This performance was difficult for Kean, his memory fading badly; his last words on stage were: “Othello’s occupation’s gone…” and he died shortly after in May of that year.

The funeral procession to Richmond Church (St Mary Magdalene) was a grand affair. Macready later recorded his feelings. Kean was placed in a churchyard vault near the church’s exterior south wall. On the wall’s exterior, Charles erected a plaque which was later removed to the inside of the church, although the tablet now seen on the west wall may not be the original; a ledger was laid in the floor of the church in 1975. His possessions, including Garrick’s sword, and all the contents of the house were sold to cover debts, raising less than £500.

Sir Henry Irving regarded Kean as the greatest of actors; Byron in 1821 described Cooke as “the most natural, Kemble the most supernatural and Kean a median of the two” (with MrsSiddons “worth all three put together”!).

Sir Henry Irving regarded Kean as the greatest of actors; Byron in 1821 described Cooke as “the most natural, Kemble the most supernatural and Kean a median of the two” (with MrsSiddons “worth all three put together”!).

Michael Gaunt pointed to the way in which actors of this period concentrated on, andmastered, a small number of Shakespearean roles – Kean had 11 – which were repeatedly performed, allowing greater depth of interpretation, expression and nuance. (It is known from post-mortem examination that Kean’s facial muscles were unusually highly developed.) The King’s Theatre (demolished in 1884) was relatively small – Drury Lane had 3,000 seats – and would have been an intimate and perfect arena in which these subtleties of performance could be displayed. Michael Gaunt spoke with great eloquence to the essence of Kean and what it was to be a star actor in the early 19th century.

[Footnote: Michael drew attention to the extensive resources of the Richmond Local StudiesLibrary where he had conducted his research on Kean’s years in Richmond and whosearchive had provided many of the pictures that illustrated his talk.]