Date/Time

Date(s) - Monday 17 January 2022

8:00 pm - 9:00 pm

Location

Duke Street Church

Categories No Categories

This talk was held in person at Duke Street Church’s Fellowship Hall,and was also streamed via Zoom. A video recording of the talk is available on our YouTube channel.

This talk was held in person at Duke Street Church’s Fellowship Hall,and was also streamed via Zoom. A video recording of the talk is available on our YouTube channel.

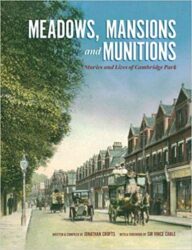

Local historian Jonathan Crofts revealed Cambridge Park with a talk based on his book Meadows, Mansions and Munitions. Cambridge House and Park’s streets and gardens have a history to rival that of neighbouring Marble Hill House and Park.

Using many illustrations and sharing stories of some of its colourful characters, Jonathan:

- covered how the original 17th-century Twickenham Meadows became the Cambridge Park estate and progressed into today’s affluent riverside suburb

- examined whether the 19th- and 20th-century Little and Foulkes families were really “dodgy developers” or “local visionaries”

- described how the area became a veritable “Belgium-on-Thames” in the First World War

- recountedhow the Thames-side munitions factory become a world-ranking ice rink and then met a contentious demise in the late 1980s.

Jonathan Crofts is the author of Meadows, Mansions and Munitions: Stories and Lives of Cambridge Park, described by former Twickenham MP Sir Vince Cable as a meticulously researched, comprehensive, beautifully illustrated history of that part of Twickenham… Jonathan Crofts has managed to unearth just about every photograph, art work, map and architects’ drawing of the area over the last few centuries and has compiled a detailed account of the characters who lived there and shaped its history and geography.”

Jonathan has lived in the Cambridge Park area of East Twickenham since 1993, and has followed local history ever since through reading, talks, walks and visits, as well as his own research and photography. He has built an extensive collection of local antique prints.

After leaving Bristol University with a degree in Modern Languages in 1986, he embarked on a career in theatre and television, including 16 years at the BBC, and latterly working all over the world as a consultant with media and broadcast organisations.

He founded Richmond Bridge Media www.facebook.com/RichmondBridgeMedia/ in 2020 with his wife, Monica Byles, who has spent over 30 years in book publishing, both fiction and non-fiction.

Jonathan’s first book is a tribute to the people of Cambridge Park, East Twickenham as much as a reflection of its history, buildings and gardens.

John Foley reports on Jonathan Crofts’ talk

You will almost certainly have walked along it; that lovely riverbank footpath leading from Richmond Bridge towards Twickenham, giving stunning views across the Thames towards Richmond Hill and Petersham. But what lies to the right of the path, invisible through the thick spinney of trees? This is East Twickenham (not St Margarets!) and it was the story of Twickenham Meadows, as this area was known for centuries, which Jonathan told us in his captivating talk.

There was no bridge at Richmond until 1777, merely a ferry, from which a country track straggled west towards the village of Twickenham, bypassing rolling fields to its south; these were known as Twickenham Meadows. Shepherds minding their flocks would have heard the shouts of river boatmen as they steered their unwieldy craft through the currents, the Thames then – and for centuries to come – being the main transport highway. Landscape paintings by various 17th and 18th century artists (shown by Jonathan, and gloriously reproduced in his newly published book) allow us to see just how remote and picturesque it all was.

The building in the early 17th century of Twickenham Meadows (the house) , at roughly the same time as that of Ham House across the river, marks a watershed in the social history of East Twickenham. The first owner of this Jacobean house was Sir Humphrey Lynd, from Dorset, a man described as “a most learned knight and zealous puritan” who had been knighted by James I. Lynd is described as “devoting his life to the cause of religion, writing energetically against the church of Rome”. The house then contained at least 26 rooms, according to hearth tax records, and was surrounded by parklands extending to 74 acres. Tragically. It was pulled down in 1937, a full examination of the house at that time – then named Cambridge House – showing that the interior contained fine rooms as well as two magnificently carved pillars of matchless beauty. (For a much fuller description, refer to Jonathan’s book where this is given in detail.)

There followed a long succession of aristocratic owners; among the most notable was Sir Joseph Ashe (1657–1686), a wealthy Somerset merchant who having supported the Royalists during the English Civil War was rewarded with a baronetcy on the restoration of Charles II in 1660. Having settled in Twickenham, Ashe was impatient to acquire more land and to increase the size of his park; this explains why today there is still the “dogleg” in Richmond Road where the Rising Sun pub and the church stand. But Sir Joseph was not just acquisitive, he was active in local affairs and we are told that he gave generously to the poor. The marriage in 1669 of his eldest daughter, Katherine, to the wealthy young William Windham of Felbrigg in Norfolk, further strengthened the Ashe family’s fortunes, and led eventually to the family name being altered by his descendants to Windham Ashe.

But perhaps the most colourful occupant of Cambridge House, as it would eventually be renamed, was Richard Owen Cambridge (1717–1802) who lived at the house (then still called Twickenham Meadows) with his family from 1751 until his death. In this, the age of elegance, life at the house reflected the brilliancy and wit of the time. There were visits from the irreplaceable Samuel Johnson, his biographer, James Boswell, and of course the one and only Horace Walpole, who wrote in 1755 describing at length the list of regular visitors and their respective occupations, ending by describing Cambridge not just as an artist or poet but as “the everything”; “the everything” quoted by Walpole referred to Cambridge’s many and varied interests, especially writing, poetry and a flair for landscape gardening, very much the latest thing then. Not only other luminaries such as Sir Joshua Reynolds, “Capability” Brown, Sir Joseph Banks, Captain Cook, Lord Chesterfield, Edward Gibbon… but also the authoress Fanny Burney, daughter of an eminent musicologist, who only left off visiting when what she thought was a romance with the Cambridges (both father and son!) failed to lead to a proposal. (She went into court service at Kew Palace where her famous diaries record the suffering of poor sick and confused George III in his later days.)

After Richard Cambridge’s death in 1802, things began to change. Richard’s son, the archdeacon, moved eventually into a smaller house nearby called Meadowbank, while the original house was leased out (to some quite illustrious tenants too). In his eighties the archdeacon sold off part of the estate he could not manage, and the Victorian residential development of the Cambridge Park estate began.

There is no space in this potted report to go through the very interesting phases of residential development by two main families of builders, the Littles and the Foulkes. Some of their unmistakable Victorian creations still stand and are worth a walk around Cambridge Park to find. No space either to describe the story of the home for “The Exiles”, nor the very interesting arrival, in 1914, of Belgian refugees who worked at the Pelabon munition works by the river throughout World War One, a tale in its own right. Recently a monument to their presence in the area was put up by the riverbank path and the Belgian ambassador was at the unveiling. After the Belgians, in the very same building as was the Pelabon munition works, came the ice rink, which was loved and cherished for years and which many must remember; its sorrowful sale to developers in the 1980s without the promised replacement rink being provided is still a very sore point for many!

For lots more detail than is possible to record here, do go to the Zoom recording, on the Society’s YouTube channel, of Jonathan’s talk. Better still, get hold of a copy of his excellent book (Meadows, Mansions and Munitions: Stories and Lives of Cambridge Park, published by Richmond Bridge Media), not only for more detailed information but also to enjoy the profuse coloured illustrations – a real labour of love!