Date/Time

Date(s) - Monday 12 September 2022

7:30 pm - 8:30 pm

Location

The National Archives

Categories No Categories

This talk, a joint event with the Kew Society, was held in the Lecture Room on the 1st floor at The National Archives, Kew. It was not streamed via Zoom.

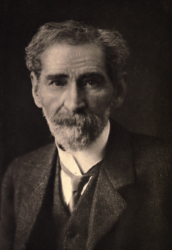

William Henry Hudson (1841 – 1922) was an Anglo-Argentine author, naturalist and ornithologist.

W H Hudson occupies a special place in the history of Richmond. He was a prominent campaigner in stopping the building of the National Physical Laboratory at Kew at the turn of the 20th century, as well as being a campaigner more broadly on protecting the wildlife of London’s parks and green spaces. His last book was A Hind in Richmond Park, completed by a friend soon after Hudson’s death.

Conor Jameson has written for The Guardian, BBC Wildlife, the Ecologist, New Statesman, Africa Geographic, NZ Wilderness, British Birds, Birdwatch and Birdwatching magazines and has been a scriptwriter for the BBC Natural History Unit. He is a columnist and feature writer for the RSPB magazine, Nature’s Home, and has worked in conservation for 20 years, in the UK and abroad.

John Foley reports on Conor Jameson’s talk

One morning in May 1874 a tall young man in his early thirties walked down the gangplank from a yellow-fever-stricken steamer, just arrived from South America, at the port of Southampton.

As Conor Jameson explained in his riveting talk, this was no ordinary young man. Bought up by his North American-born parents on an isolated farm in the pampas grass farming districts near Buenos Aires, he had no formal schooling, but was self-educated, having read tomes of his parents’ extensive home library in their whitewashed farmhouse. William Henry Hudson, despite his lack of education, was already a distinguished figure in his chosen field; the close and acute study of nature, especially of ornothology. His childhood and youth had been spent in the open fields and woods of Patagonia. He had already received recognition from such bodies as the Smithsonian Institution and Zoological Society of London for his reports of local birdlife (including the discovery of two new species of birds), and had entered into somewhat direct correspondence with the great Charles Darwin concerning characteristics of South American woodpeckers (as a result of which Darwin had been forced to modified his original opinions).

Although Argentine-born as a result of his family background (his grandfather had come from Devon and his youthful reading was of English poets, classics and Gilbert White, the Hampshire naturalist) Hudson felt strongly drawn to England. Yet his arrival was hardly welcoming. The rich aroma of hops streaming from the Southampton breweries shocked him. Instead of taking the first train to London, Hudson announced his intention of taking a horse and trap and exploring the local countryside, explaining that he wanted to meet English birds (and he quickly discovered a new species of nightingale!). During his tramps around the country and later in London he frequently slept outdoors in the open.

In London he explored the city without maps. Whilst repelled by the city rat-race of scurrying people, Hudson loved the rooks and especially the rows of elm trees in St James’s Park-he was horrified later when they were felled. Hudson had two special hates: stuffed birds and animals and especially the Victorian plumage trade in which birds’ skin and feathers were made into fashionable ladies’ hats. Partly due to Hudson’s efforts and his support of those influential in forming what we now know as the RSPB, the plumage trade was banned by an Act of 1922. (Queen Victoria herself joined in this campaign.) Hudson was socially direct (uncouth?) and tended to fall out with eminent professional naturists to whom he was introduced. But he started earning money by producing and contributing to books on ornothology which brought him further income and esteem. Other naturalist books followed his experience of living rural life as it then was on the Sussex Downs.

Always a loner, he made a surprisingly successful marriage with a former opera singer some years his senior, who ran boarding houses in Bayswater. (He had fallen in love with her voice.) Hudson had begun to write prolifically and, from his researches, produced exhaustive tomes on the history of lost British birds. He discovered Kew Gardens, where he spent much time, and his opinion was strongly influential in defeating a 1900 proposal to site the newly proposed National Physical Laboratory there.

His prestige and writing attracted the notice of many successful and influential people. The Foreign Secretary at the time of the outbreak of war in 1914 was a great friend (Sir Edward Grey spent his time away from Government fishing in Hampshire) and was an ornithologist. Other eminent admirers included John Galsworthy, the Nobel prizewinning novelist (who considered Hudson the greatest living writer of English), the novelist George Gissing, the poet Edward Thomas, the Victorian explorer naturalist Marianne North, and from afar Theodore Roosevelt, then US president. Hudson’s writing success brought him membership of a literary circle though he rather looked down on fine dining and was a poor public speaker.

His wife had become infirm and moved to Worthing where she died; Worthing happened to be where Richard Jefferies, another eminent naturalist writer friendly with Hudson, lived. Indeed, when Hudson died, he too was buried at Broadwater cemetery, Worthing next to his wife and Jefferies. But it is a sign of just how high Hudson stood in the minds of his contemporaries that, following his death, a stone memorial in rather daring contemporary style by Epstein was built on the edge of Hyde Park.

As Conor reassured us, Hudson is still in print. Not only that, in Argentina he is still famous; a railway station and a suburb of Buenos Aires bears his name, while his parents’ farm is preserved as a monument. At one stage his fame had spread to Japan – to such an extent that the text of his autobiography Far Away and Long Ago was used to teach Japanese students the basics and beauty of written English.

Some people consider that his best work is The Shepherd’s Life of 1910, describing the surviving shepherds of South Wiltshire and in particular their memories. Hudson lived in their homes and talked to them by their home fires. Reading it, you enter into a world now completely vanished. On a recent visit to the village where Hudson temporarily lived 112 years ago, the village shop proprietoress exclaimed ”Oh yes, The shepherd!” and gave directions to the very cottage where Hudson had lived. Definitely not forgotten then, and ready for fresh discovery by historians and nature lovers in the twenty first century!